US debt ceiling shenanigans, a repeated source of market volatility over the past decade or so, are rearing their head once again. After tentative progress was made last week negotiations look to have reached an impasse. Reportedly, the Republicans are continuing to push for sizeable reductions in government spending, particularly in areas such as healthcare, education, and housing, while also maintaining high spending on defense and the Trump-era corporate tax cuts. The two sides have agreed to resume talks with President Biden and House Speaker McCarthy set to meet on Monday, but things clearly remain fluid.

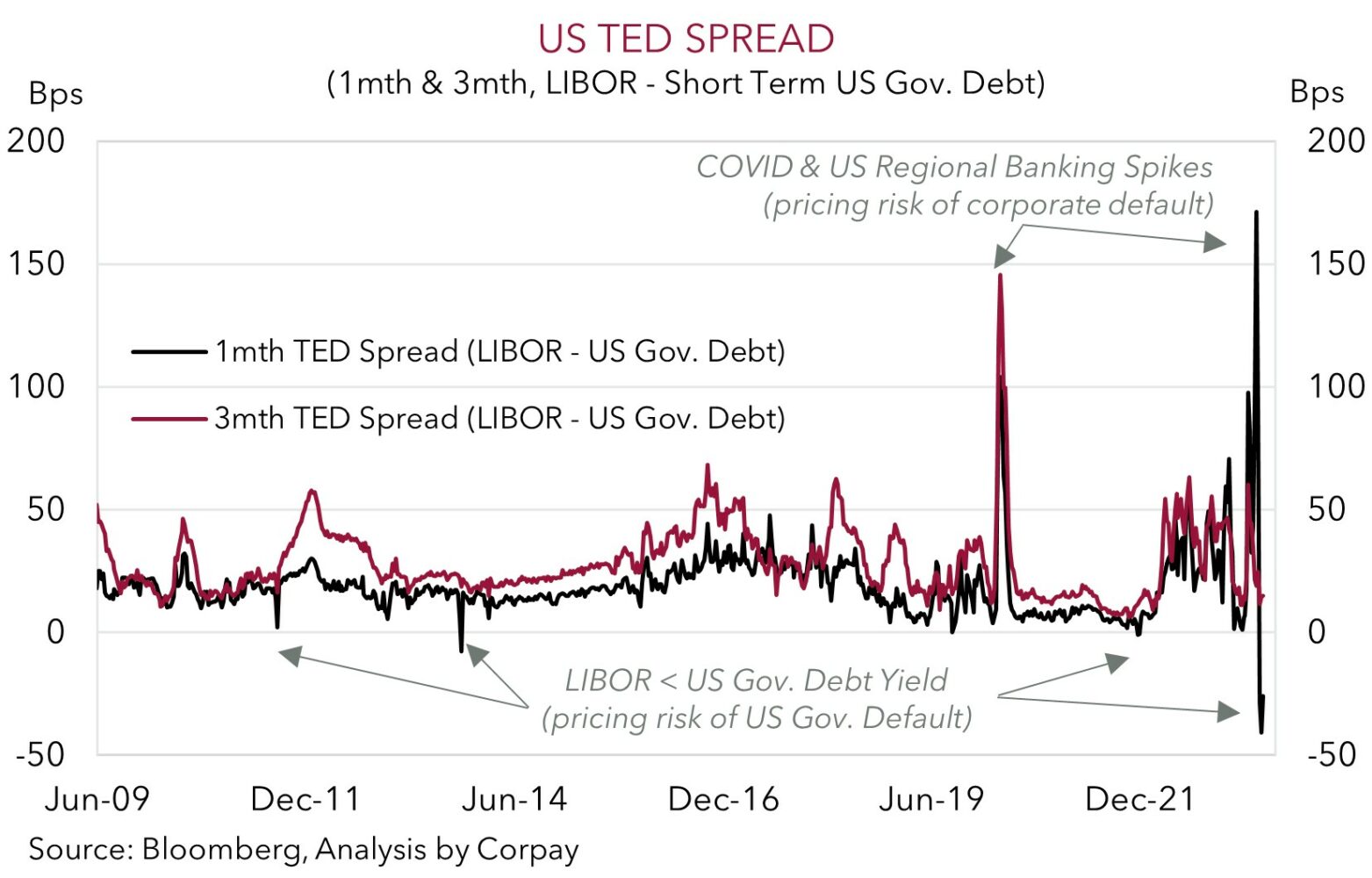

The clock is ticking for a deal to be reached. This issue should remain front-of-mind for investors (and be a source of volatility) over the near-term given the importance a resolution is reached and the potential chain of events that could be unleashed if it isn’t. As shown in the chart below, the US TED spread (i.e. the difference between the yield on short-dated US Government and Corporate debt) has shifted significantly, with nervous participants demanding a higher risk premium to hold US government debt over the next month due to the greater perceived chance of default.

Some background & the current state of play

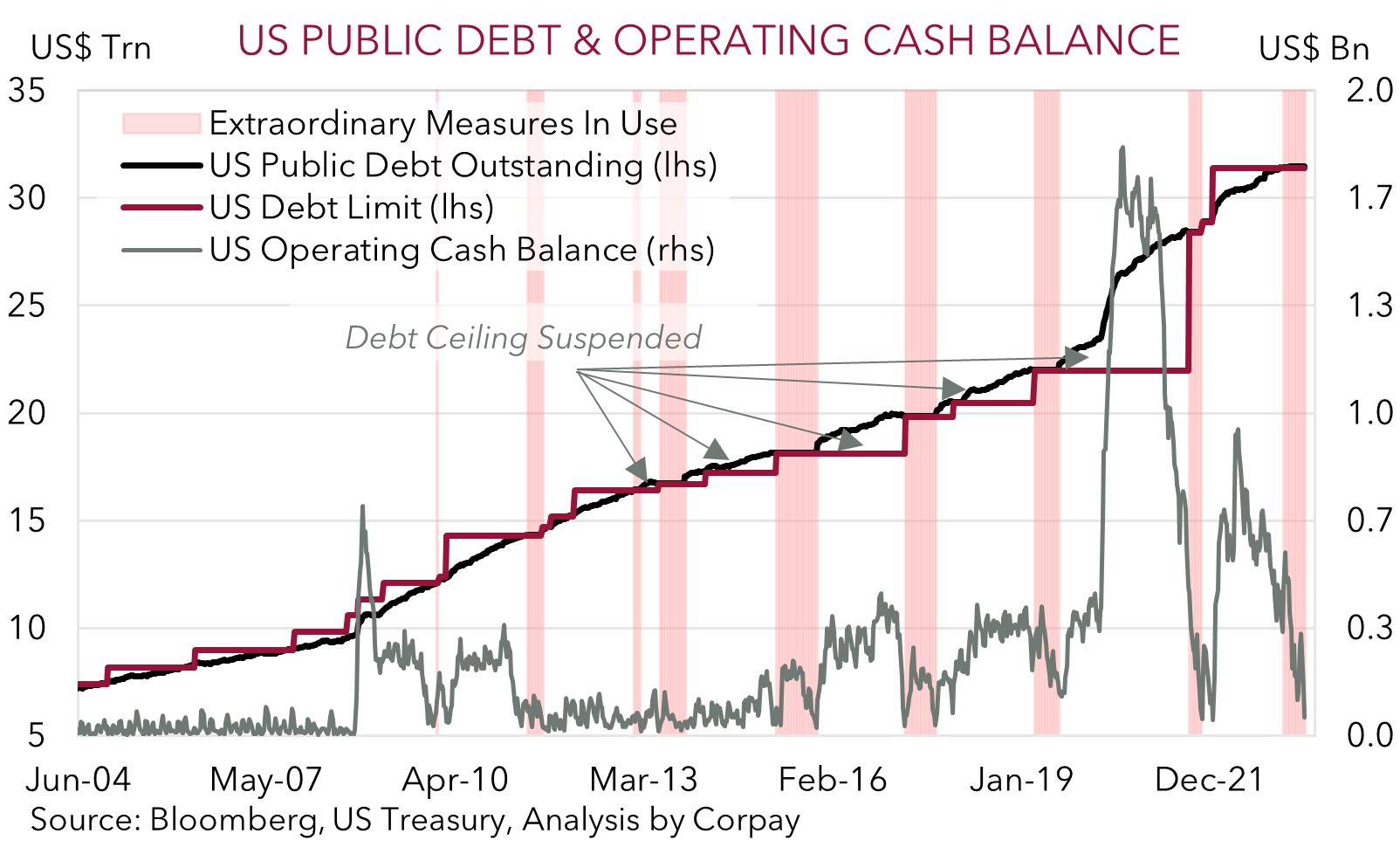

For those unfamiliar, the ‘debt ceiling’ is the statutory limit on the amount of debt the US Federal Government can issue to fund its operations and pay its obligations. Once it is reached the government cannot borrow additional money without Congressional approval. Raising it should be a mechanical process whereby the ‘ceiling’ is increased (or suspended) as it draws near given government spending rises over time with inflation and a larger economy, and as the US remains mired in a budget deficit. The last time the US recorded a budget surplus was in 2001. As shown below, the debt ceiling was increased repeatedly throughout history, however the process has become quite challenging over recent years due to the fractured nature of US politics.

Importantly, if the debt ceiling isn’t raised (or suspended) then the US Treasury cannot meet future financial obligations, including payments for social security, Medicare, and interest on the US’ burgeoning debt pile. Failure to meet an obligation could trigger a ‘technical’ default by the US Government. Past political brinksmanship has meant that the US has approached this Rubicon, but never crossed it. In August 2011 and October 2013 things went down to the wire, with the disorderly 2011 episode ultimately triggering a US credit rating downgrade by S&P.

In terms of the current state of play, US public debt reached the ceiling in January 2023. The US Treasury has been employing “extraordinary measures” such as dipping into cash reserves or suspending the reinvestment of securities into public benefit funds to keep paying the bills since then. Unfortunately, these measures have a limit. And we look to be in the home stretch with the ‘x-date’ (i.e. when the US won’t be able to pay an upcoming obligation) coming into view. Just like a simpler household budget, the ‘x-date’ is sensitive to incoming revenue and expenditure flows, so no concrete day can be given. US Treasury Secretary Yellen has stated that the ‘x-date’ could be as early as 1 June, though we would point out that the US Treasury has in the past tended to be conservative in its assessment (possibly to create an added sense of urgency to get a deal over the line).

According to the bipartisan Congressional Budget Office there is a “significant risk” that it occurs “at some stage in the first two weeks of June”. It has also been suggested that if there is enough cash and/or the US Treasury can juggle the books by pulling levers such as prioritizing debt repayments over paying federal employee wages or social security payments until 15 June, then the quarterly corporate tax receipts that are scheduled to flow into the government’s coffers and additional “extraordinary measures” that become available could kick the can down the road to late-July. Nevertheless, as things stand, we are talking about a potential ‘x-date’ window of weeks, not anything longer, with an agreement needed to avoid unnecessary turbulence and negative impacts that could compound the unfolding slowdown due to higher interest rates, tighter credit conditions, and cost of living pressures.

Market reactions: past & present

Sanity prevailing and some type of deal being struck, either to raise or temporarily suspend the debt ceiling, seems to be the base case for most market participants. However, this would require give and take from both sides of US politics, and as the recent breakdown in talks shows the path forward may have more twists and turns to come. Indeed, there look to be many parallels with the current situation and the 2011 experience given the late start to official negotiations and hostile politics. Back then the Republican-controlled House of Representatives (who clearly have an eye on the 2024 Presidential Election this time around) insisted on budget cuts without tax increases, while the Democratic-controlled Senate and the Obama Administration sought a balanced approach.

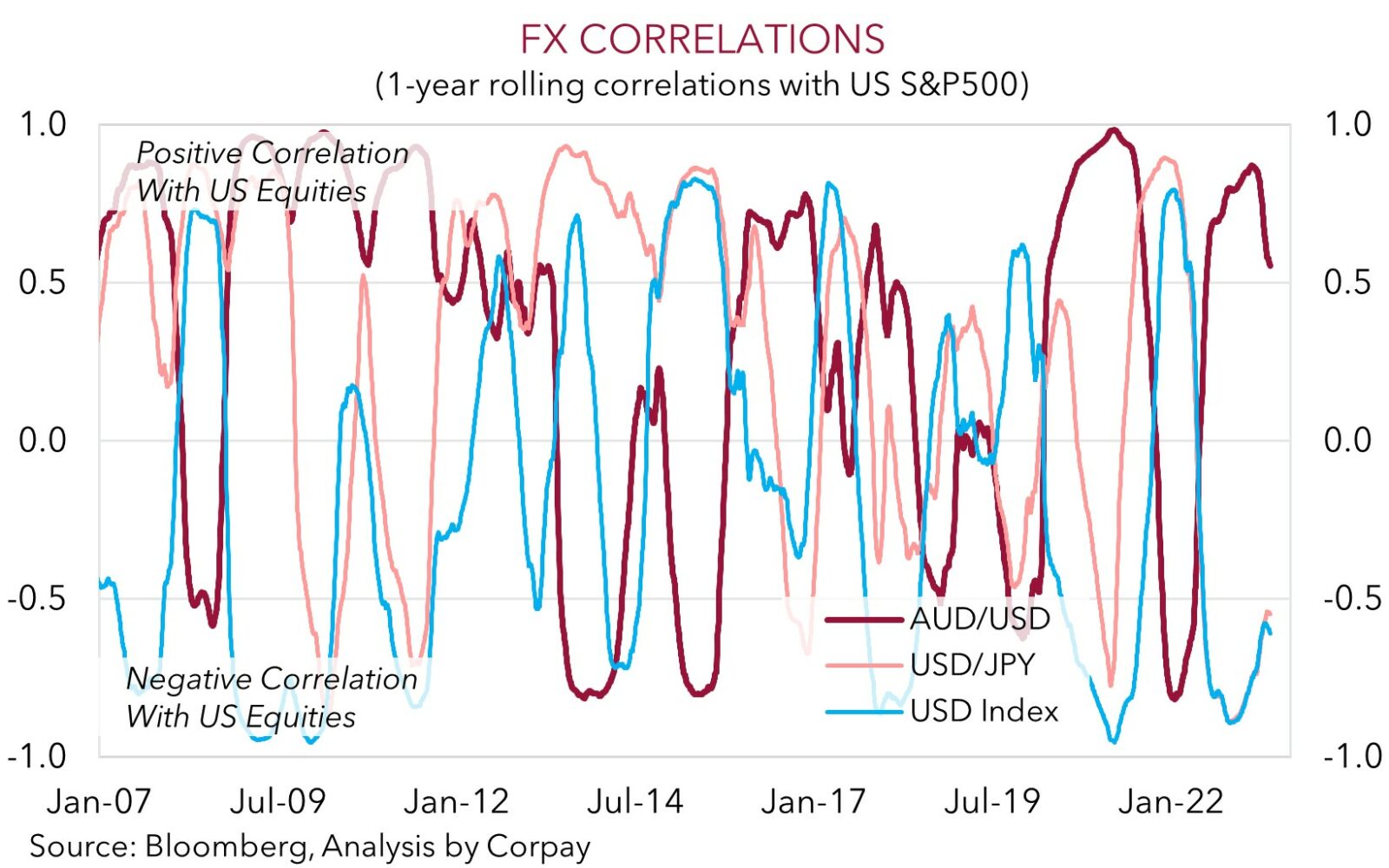

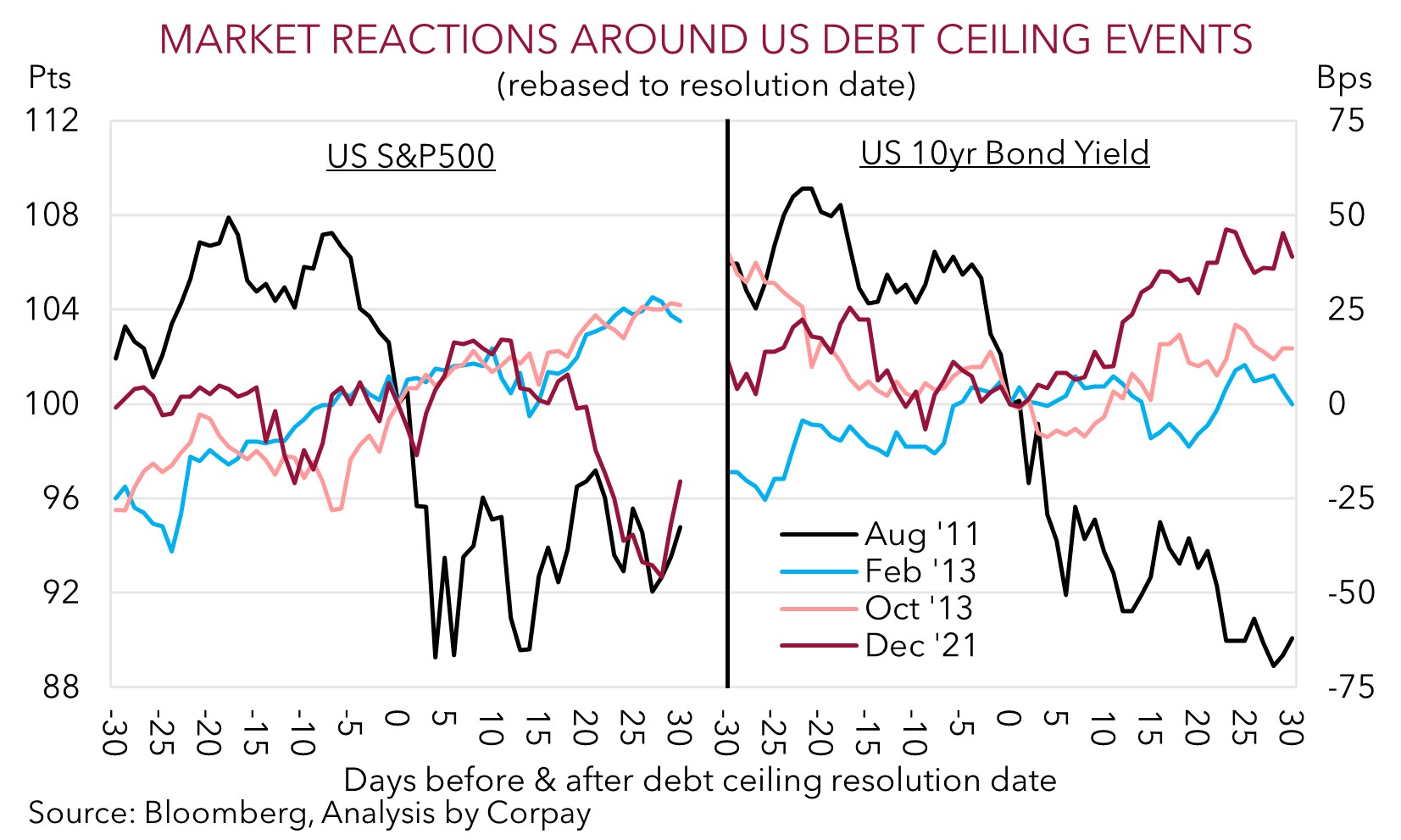

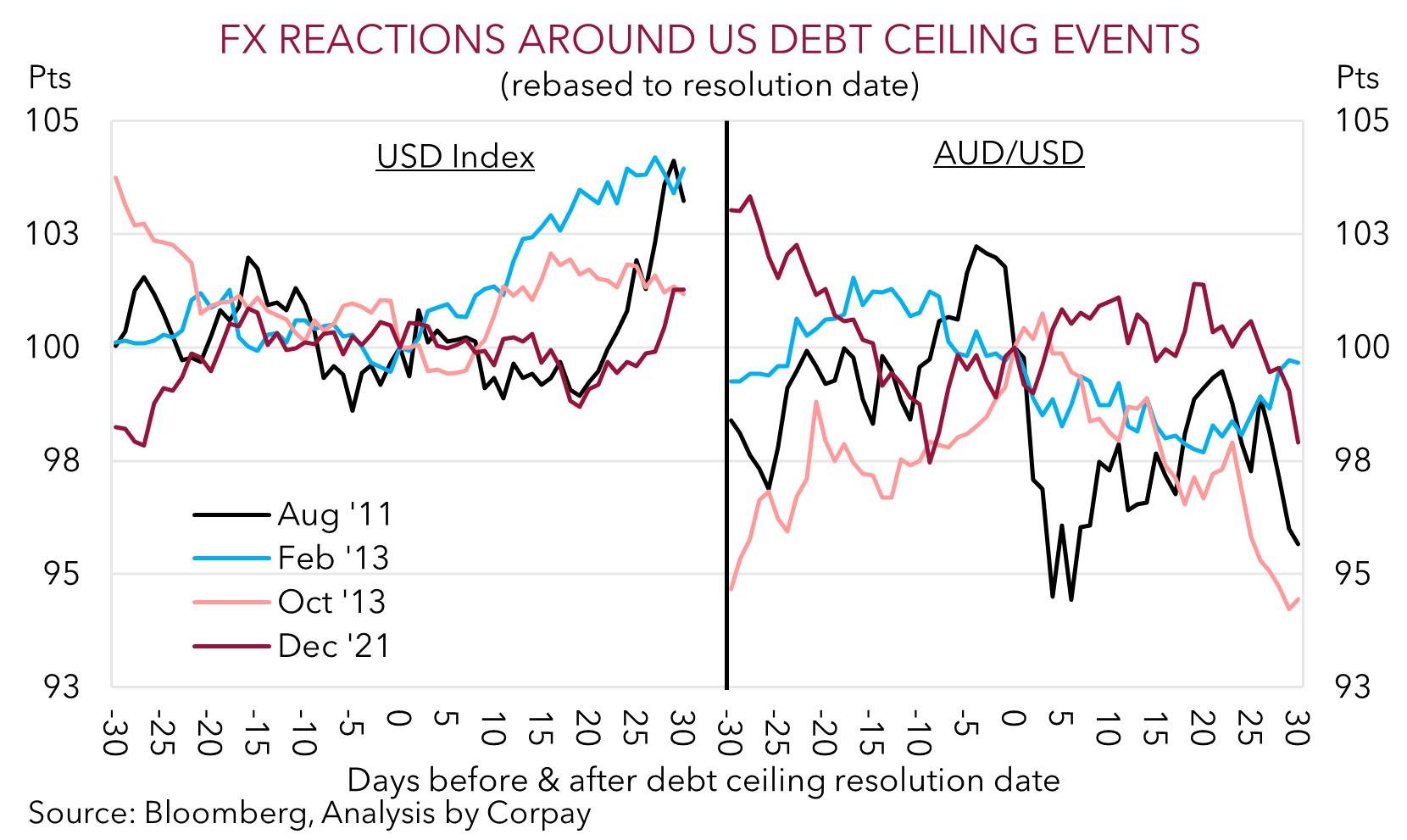

Financial markets move on the probability of an outcome, and what is factored in matters. The longer the current tricky negotiations drag out and the closer the ‘x-date’ becomes, the higher anxiety levels (and volatility) are likely to go, in our view, especially as many asset classes don’t look to be pricing in much of a downside scenario. Looking back, we found that in past more difficult debt ceiling episodes, as investor nervousness grew US equity markets and bond yields fell as risks of a negative outcome lifted. In FX, while the USD Index initially lost a little ground (before bouncing back) this was predominately against currencies like the EUR and JPY, cyclical ones like the AUD that are correlated to risk assets such as equities declined. Although we would highlight that the broader environment at the time also needs to be considered. During the 2011 iteration it wasn’t just US issues at work. The Eurozone sovereign debt crisis was raging with Greece in the middle of getting bailed out.

As discussed above, we believe volatility could lift if the current impasse drags on and odds of a US default rose. The flow through drag on growth expectations, coupled with a possible ‘risk off’ reaction (i.e. equities, bond yields, and commodity prices lower, and wider credit spreads) could, in our judgment, weigh on the AUD and broader Asian FX currencies. Our analysis finds that the AUD’s correlation to the US equity market over the past year has been on par with where it was in the year ahead of the 2011 debt ceiling episode.

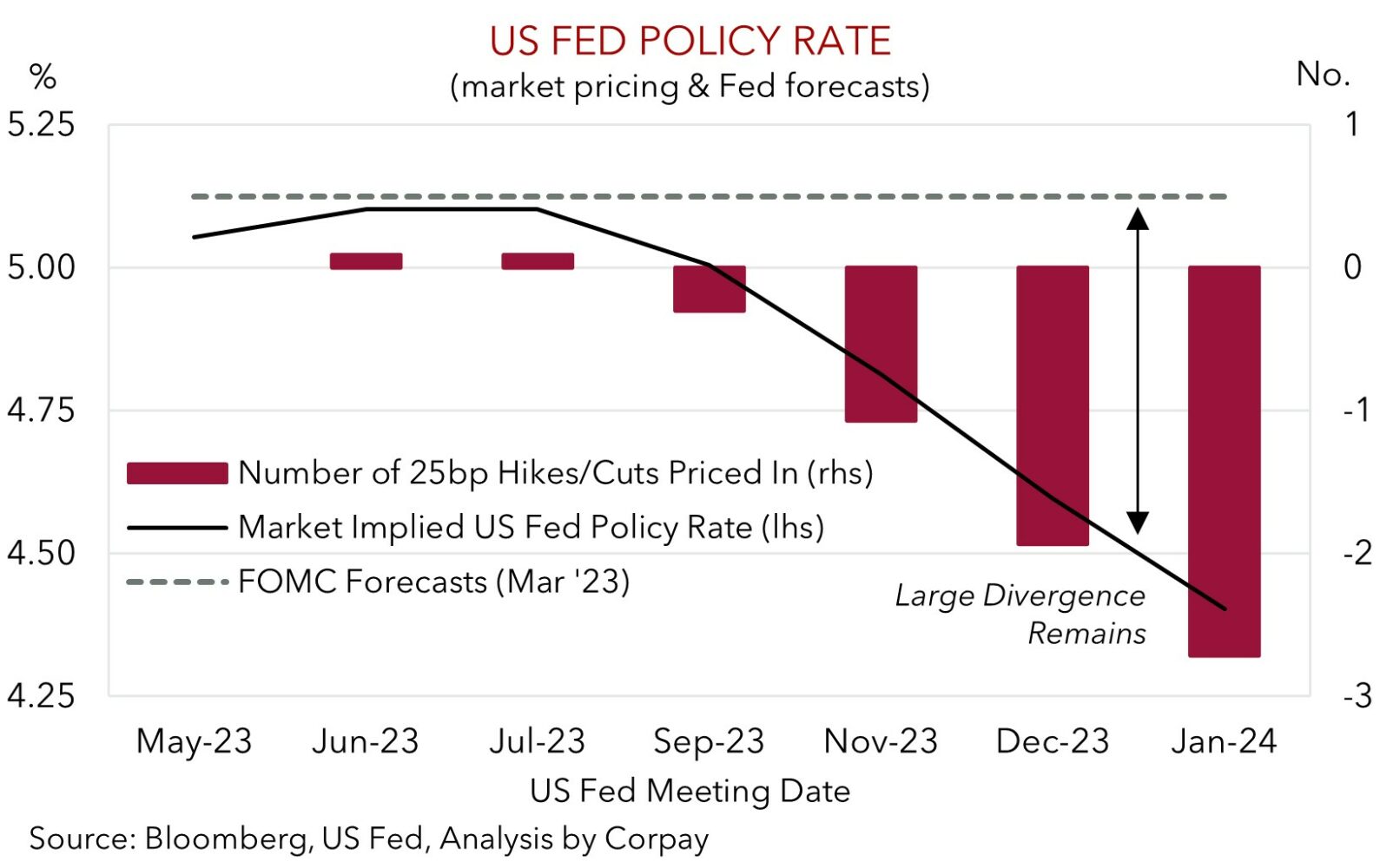

Indeed, even on the assumption that a debt ceiling deal is reached, we doubt any knee-jerk rebound in the AUD will extend too far. Fundamentally, the global economy is slowing, with China’s post lockdown recovery faltering. We are anticipating the global downturn to intensify over the next few months as tighter credit conditions constrain activity, which in turn should drag on commodity demand. And in the US we remain of the view that while the US Fed rate hiking cycle may have reached its end, a shift to a cutting cycle could be a long way off. We think that pricing for multiple rate cuts by the US Fed over H2 is unlikely to materialise given the US’ inflation problem and tight labour market, and especially if the debt ceiling can be resolved without substantial reductions in government spending. In our opinion a further paring back of US rate cut bets could give the USD more of a boost.