The decisive victory by former President Trump in the 2024 US election and elevated odds the Republicans also sweep Congress has generated bursts of market volatility over the past few sessions. This might be a taste of things to come. The election result shouldn’t be viewed as a ‘shock’ as it was 8 years ago. The outcome was in line with the signal various opinion polls and probability gauges had been pointing to for several weeks. Nevertheless, as we had forewarned in our prior research, a Trump win (particularly if it was compounded by Republican victories in both chambers of Congress) may re-shape the growth, inflation, interest, and FX outlook. And this is what markets have started to contemplate (see Market Musings: US election – FX inflection point).

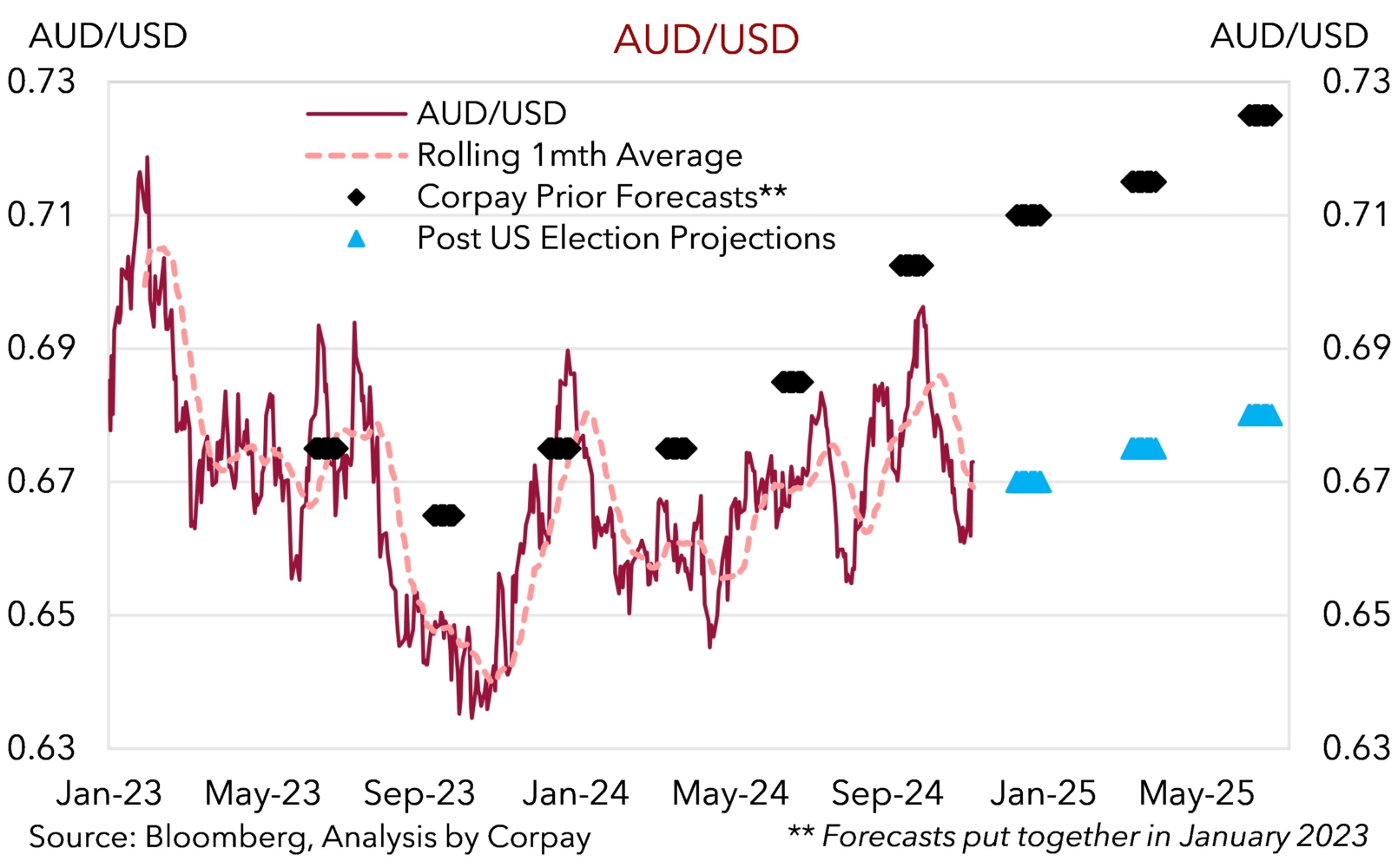

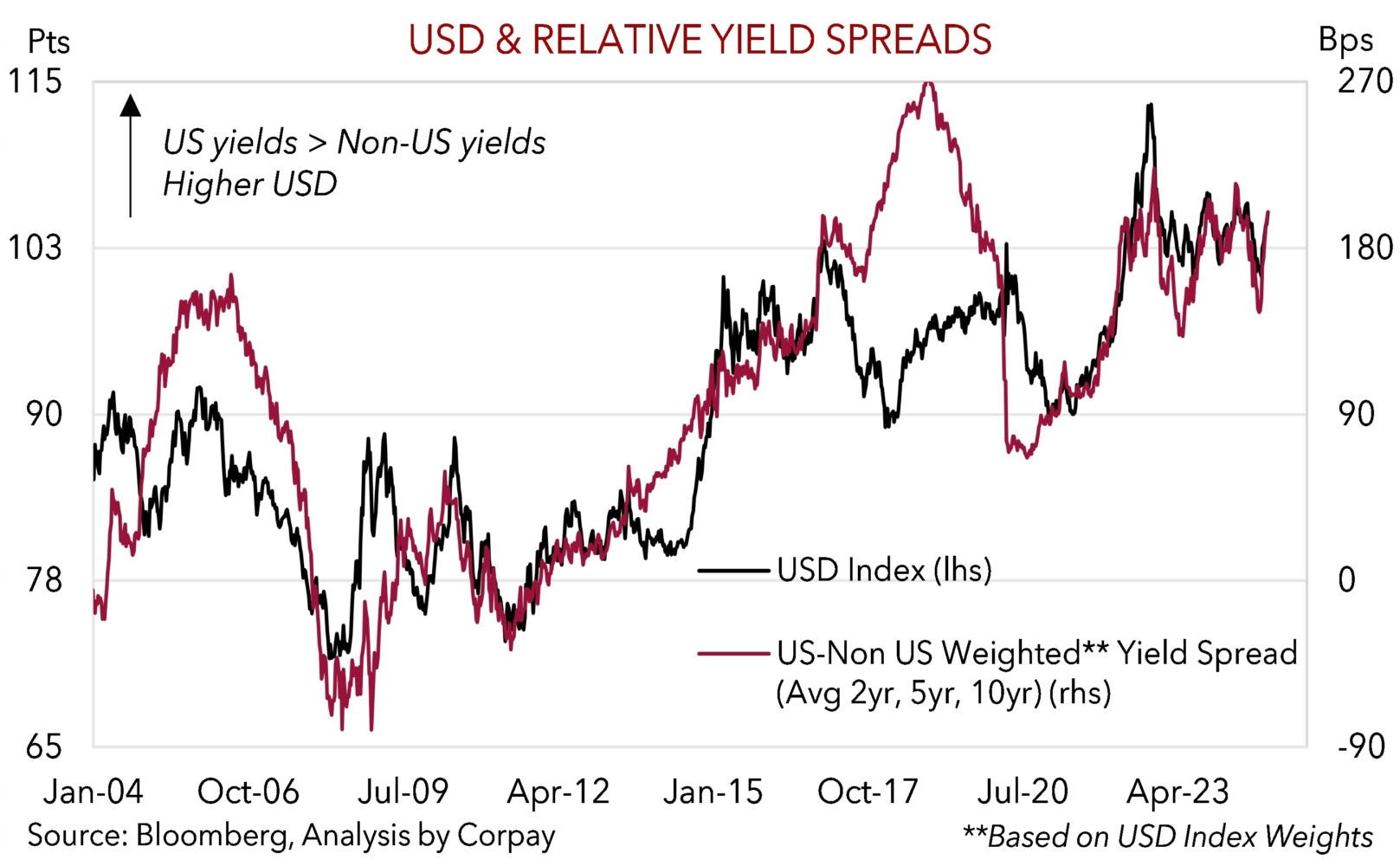

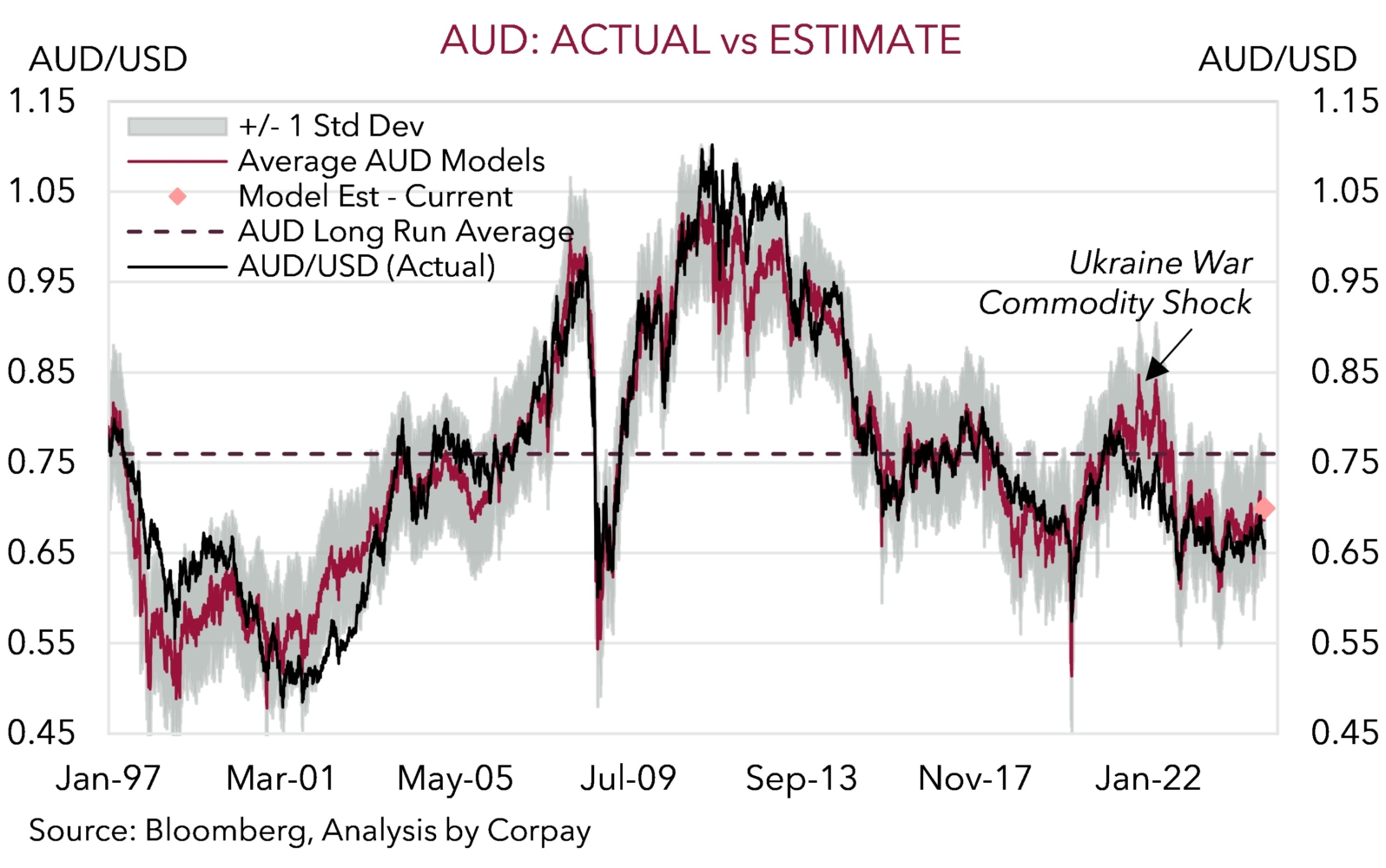

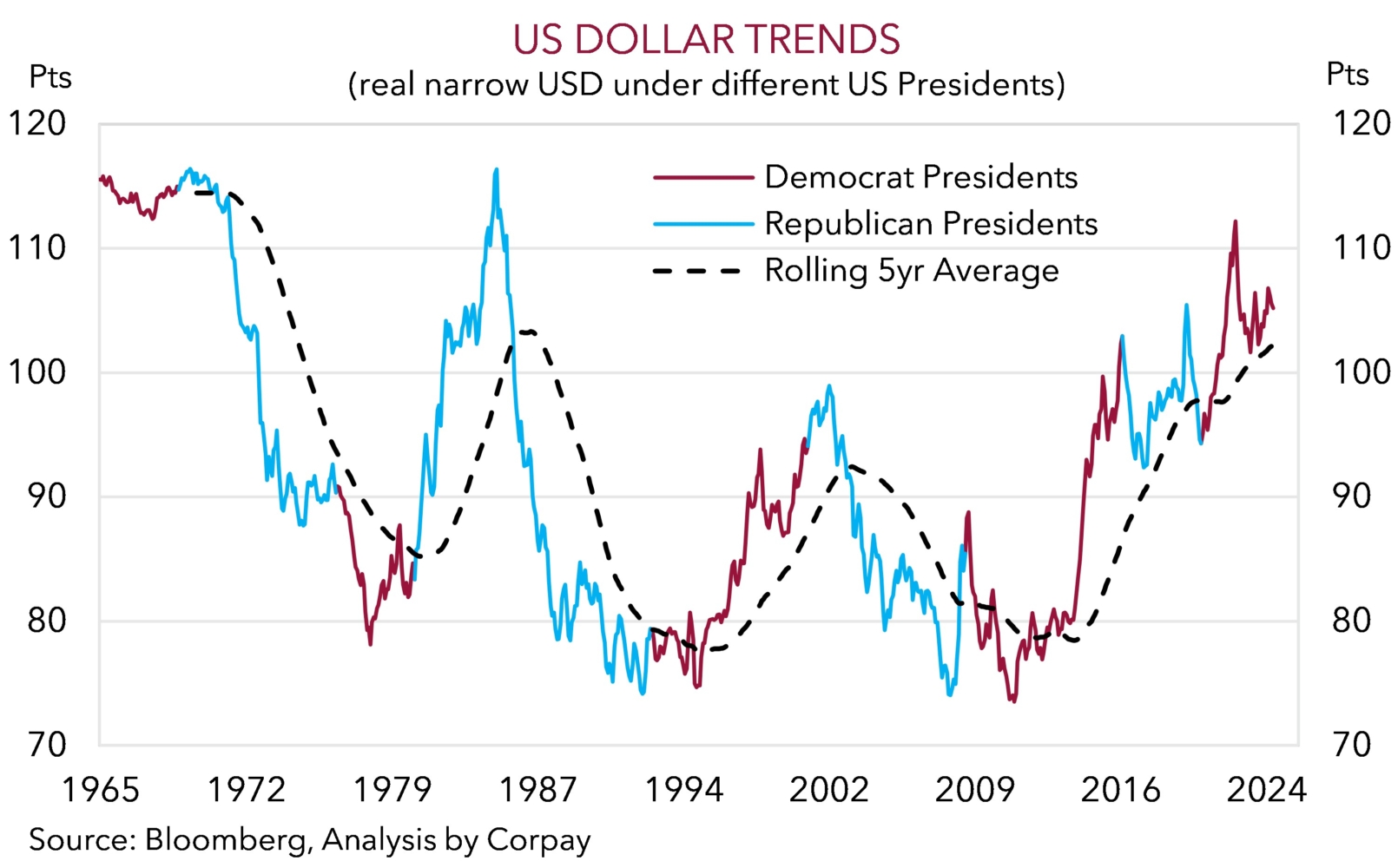

As the old saying goes, “when the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”. As such, as per the risk guidance outlined in our pre-US election note, we believe the various dynamics that look set to be unleashed in President Trump’s second term could see the AUD hover in the mid-$0.60s over the next few quarters rather than edge up to the low-$0.70s as we had long projected and broader consensus had converged towards recently (chart 1). Bottom line, we think the AUD will probably average a slightly lower level over the next 12-months than what it could have, and expectations about the AUD’s medium-term upside potential should be recalibrated. This largely stems from our judgement that most election promises will come to life and a Trump policy mix of large-scale trade-tariffs, greater fiscal spending, and measures to curb US immigration generate an (unwanted) inflation impulse which in turn prevents the US Federal Reserve from lowering interest rates as far as it might have (chart 2). This, coupled with macro and geopolitical uncertainty, possible downward revisions to already tepid global growth, and Trump unpredictability points to a stronger for longer USD. Though this may be better reflected in currencies such as the EUR, CNH, NZD, and lesser extent the JPY than the AUD, in our view.

That said, while these evolving positive USD dynamics should act to constrain the AUD’s medium-term upside, we don’t think it is likely to sustainably fall much below recent levels. It isn’t a one-way street and several counteracting forces need to be considered. Outcomes compared to expectations matter in markets and in our assessment a degree of ‘bad news’ already looks baked into the AUD given it is tracking at a ~3 cent discount to the average of our ‘fair value’ models (chart 3). Indeed, unlike the 2016 US election when a Trump victory was a genuine surprise and this abruptly jolted markets, as illustrated by the USD’s underlying revival since end-September (which corresponded with a swing towards Trump in the polls) the 2024 win was somewhat anticipated. More broadly, the US’ economic outperformance over the past few years and other fundamentals have already been keeping the USD above levels prevailing in late-2016 for a while (chart 4).

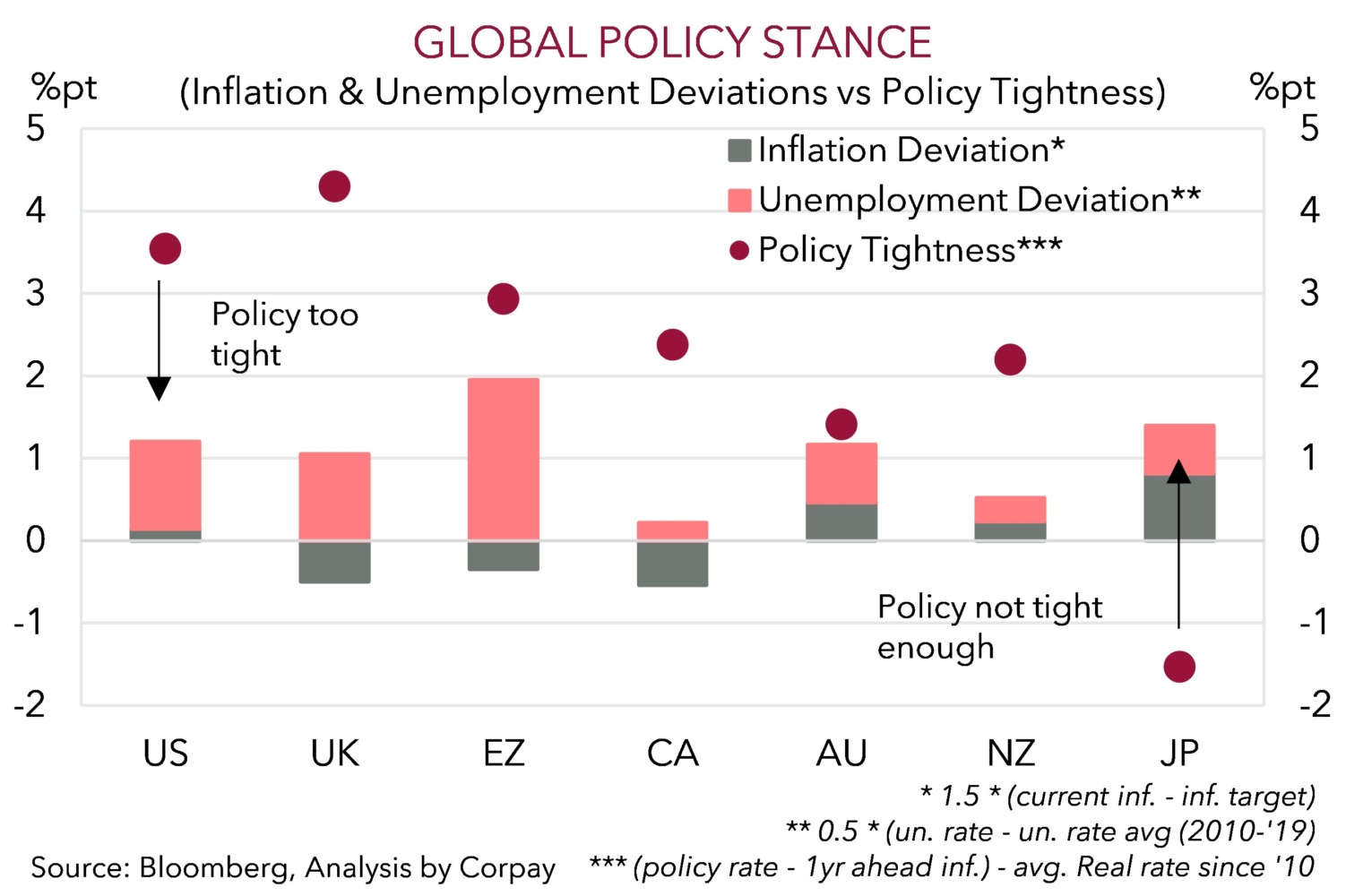

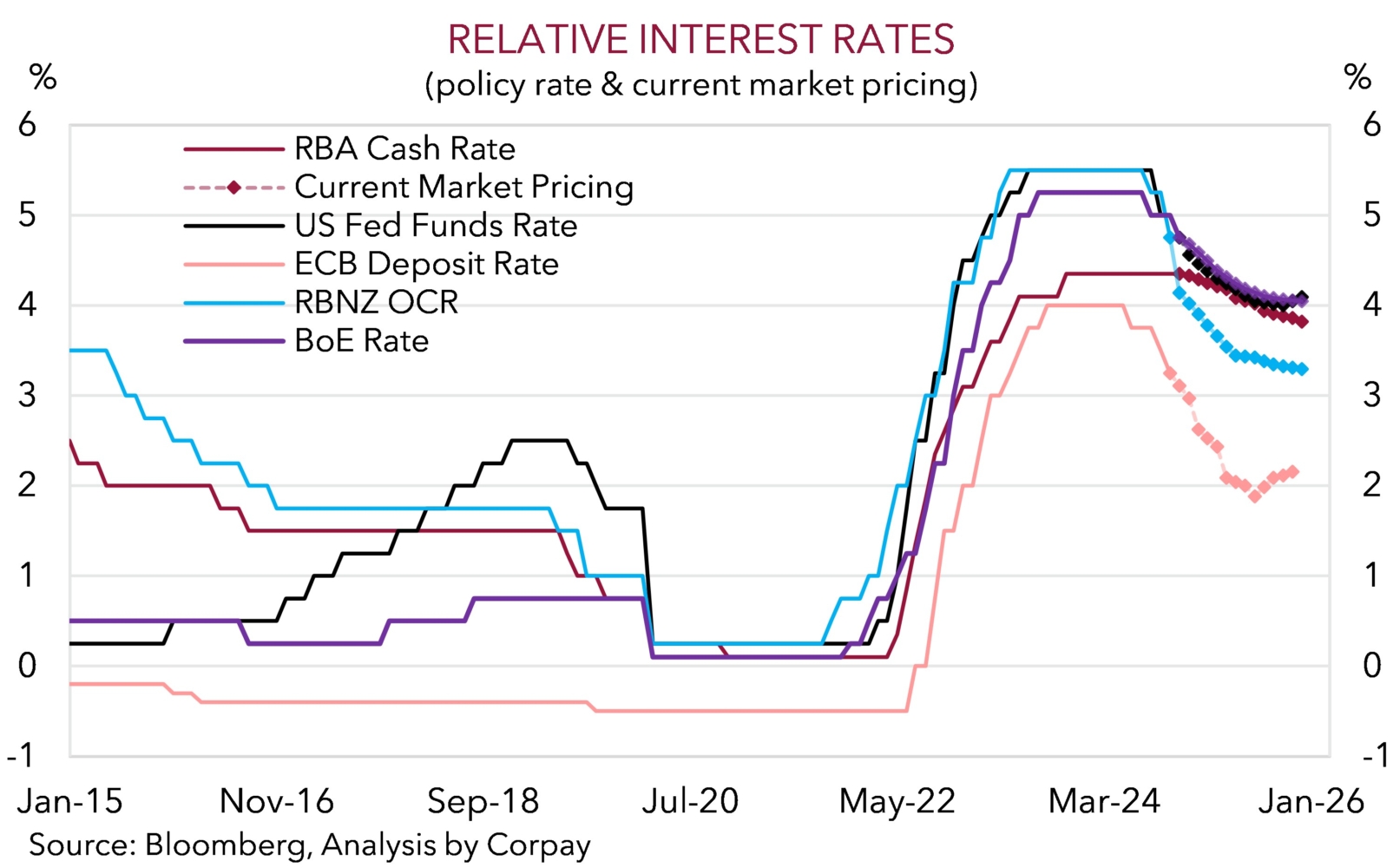

Importantly, it also shouldn’t be forgotten that FX is a relative price, and several factors remain in the AUD’s favour, especially when it comes to several AUD-crosses. For example, the resilience in the Australian labour market, stickiness in core inflation due to elevated levels of aggregate demand on the back of strong population growth, and fiscal/income support via tax cuts underpins our long-held view that the RBA will at the back of the pack when it comes to interest rate cuts. Our policy stance modelling shows that outside of the Bank of Japan, which is still behind the curve and should deliver more rate hikes, the RBA doesn’t need to rush to the exit. The RBA’s settings are, partly by design, not as ‘restrictive’ as its peers (chart 5). We continue to forecast the start of a gradual and modest RBA easing cycle in H1 2025. This is in stark contrast to other major central banks such as the ECB, RBNZ, Bank of Canada, and Bank of England, that have already started to reverse course (chart 6).

We would also highlight that policy trends between the RBA and US Fed are also in a different spot compared to when Trump first came to power in 2017. Back then the majority of Trump’s first two years as President coincided with the US Fed delivering a string of rate rises, at a time the RBA was under pressure to provide more growth support. The current debate is centered on how much further the US Fed might lower rates in 2025, not whether it will hold steady or re-start hiking. This was on show overnight with the US Fed delivering its second rate cut, and signaling it remains on a path down towards ‘neutral’ with the Trump policies not on its radar until they are passed into law.

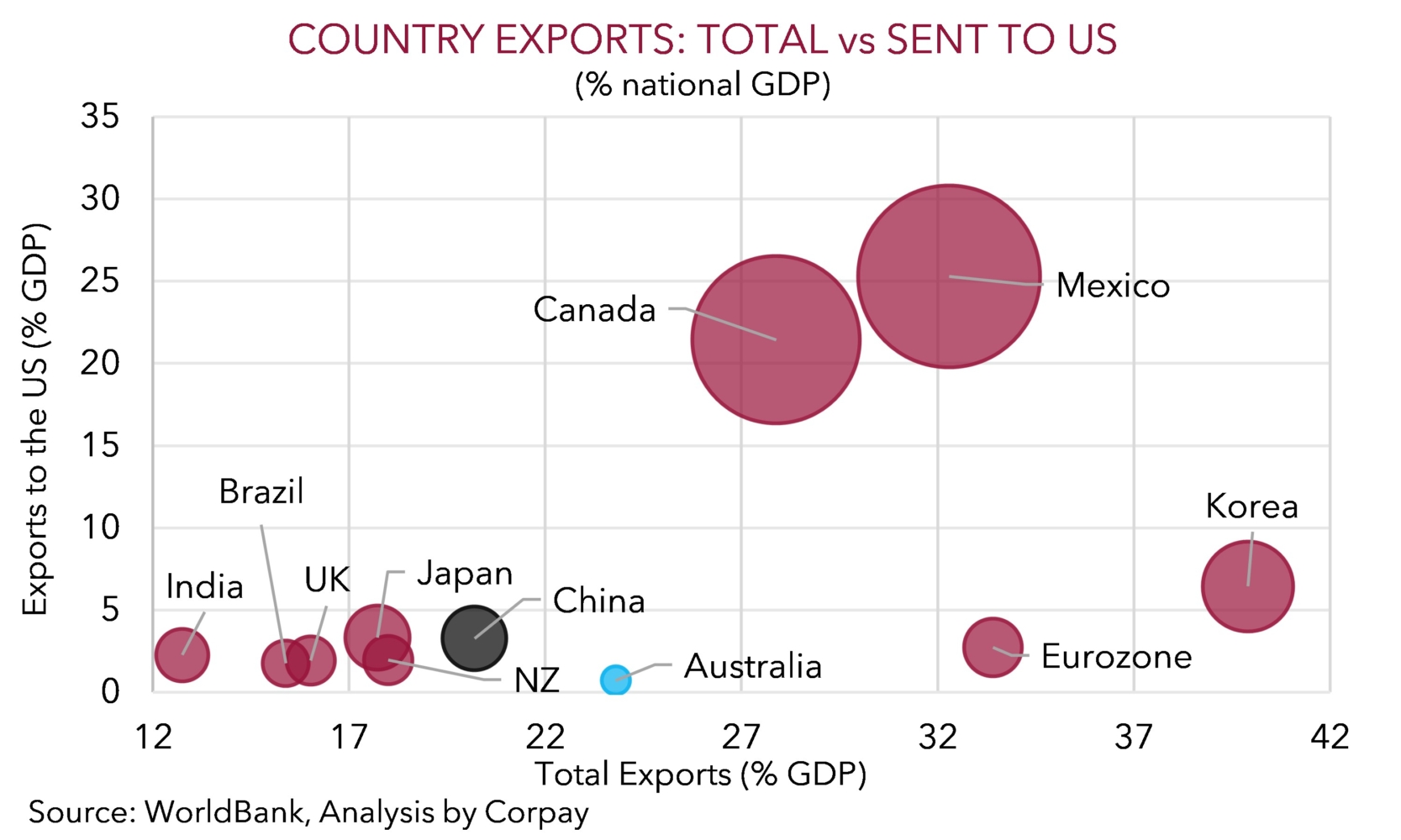

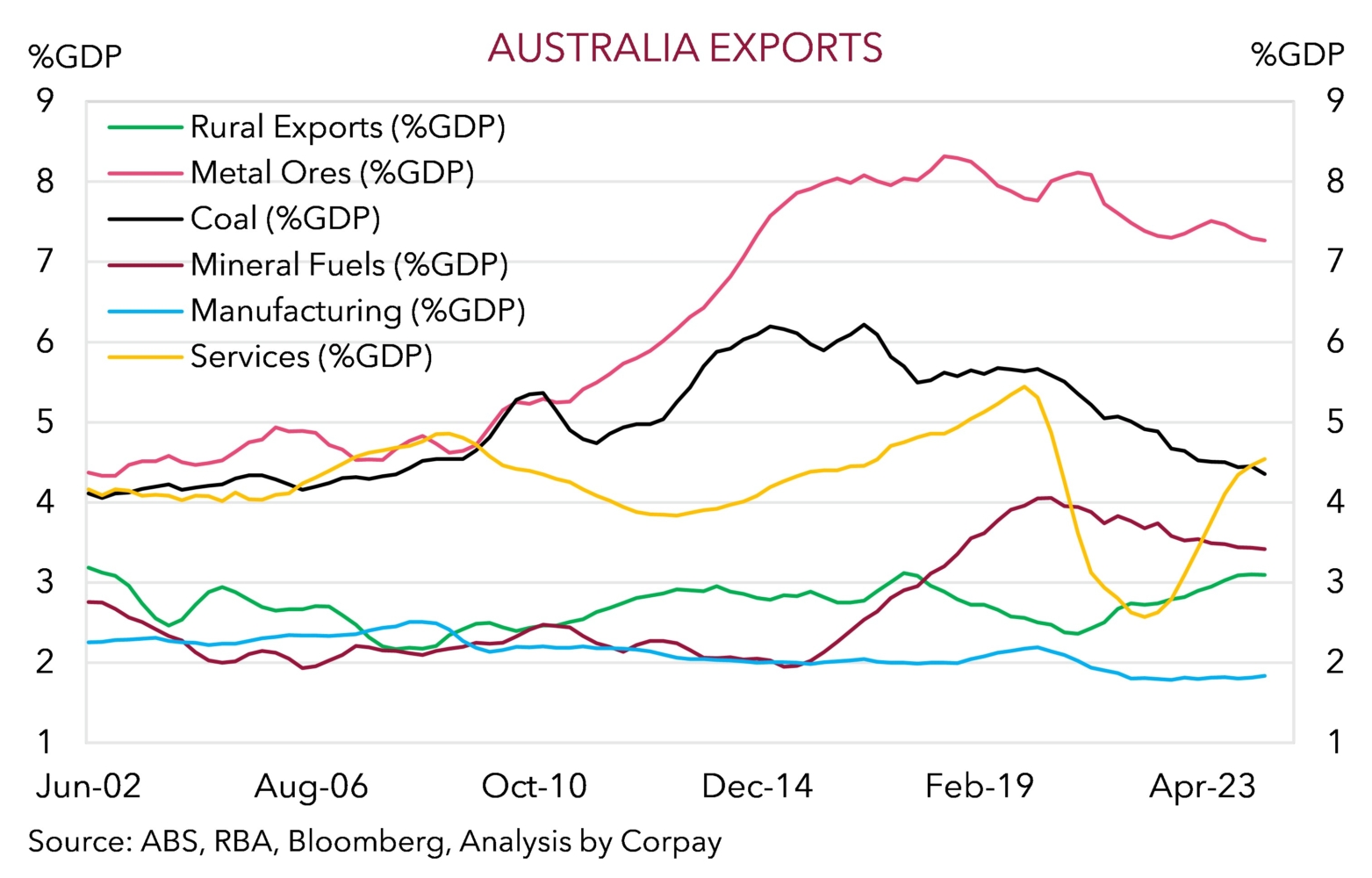

Over the medium-term we think the diverging trends between the RBA and other central banks should cushion potential downside in AUD/USD via the AUD support afforded versus EUR, CAD, NZD, CNH, and GBP. Moreover, as our chart illustrates, when it comes to Trump 2.0 trade policy, while China is facing the highest tariff severity (assuming Trump’s actions match his ‘hawkish’ pre-election rhetoric) other nations (e.g. Canada, Mexico, the EU, Korea) face greater economic consequences as their exports to the US are a greater share of national GDP (chart 7). If the rubber hits the road, central banks in these nations may offset trade disruptions via even more monetary policy easing.

We believe these possible negative offshore growth/interest rate pressures, Australia’s rather tariff-insulated export basket due to minimal domestic manufacturing (chart 8), and chance authorities in China attempt to counter any US tariff-induced export pain via steps to bolster commodity-intensive and internally focused infrastructure investment could also be relative AUD supports. This is the area Australia’s key exports are plugged into. We doubt the Australian economy will be completely immune from global turbulence created by a tit-for-tat trade war because of drags from indirect trade and confidence/uncertainty channels. However, it may be better placed to navigate rough waters than others thanks to limited direct exposures and/or policy offsets.