A modest improvement in risk appetite is washing across markets after a trade deal between the US and Japan proved less economically-damaging than feared. The dollar and Treasury yields are holding steady, North American stock indices are printing gains at the open, and risk-sensitive units like the Australian and New Zealand dollars are climbing against their peers.

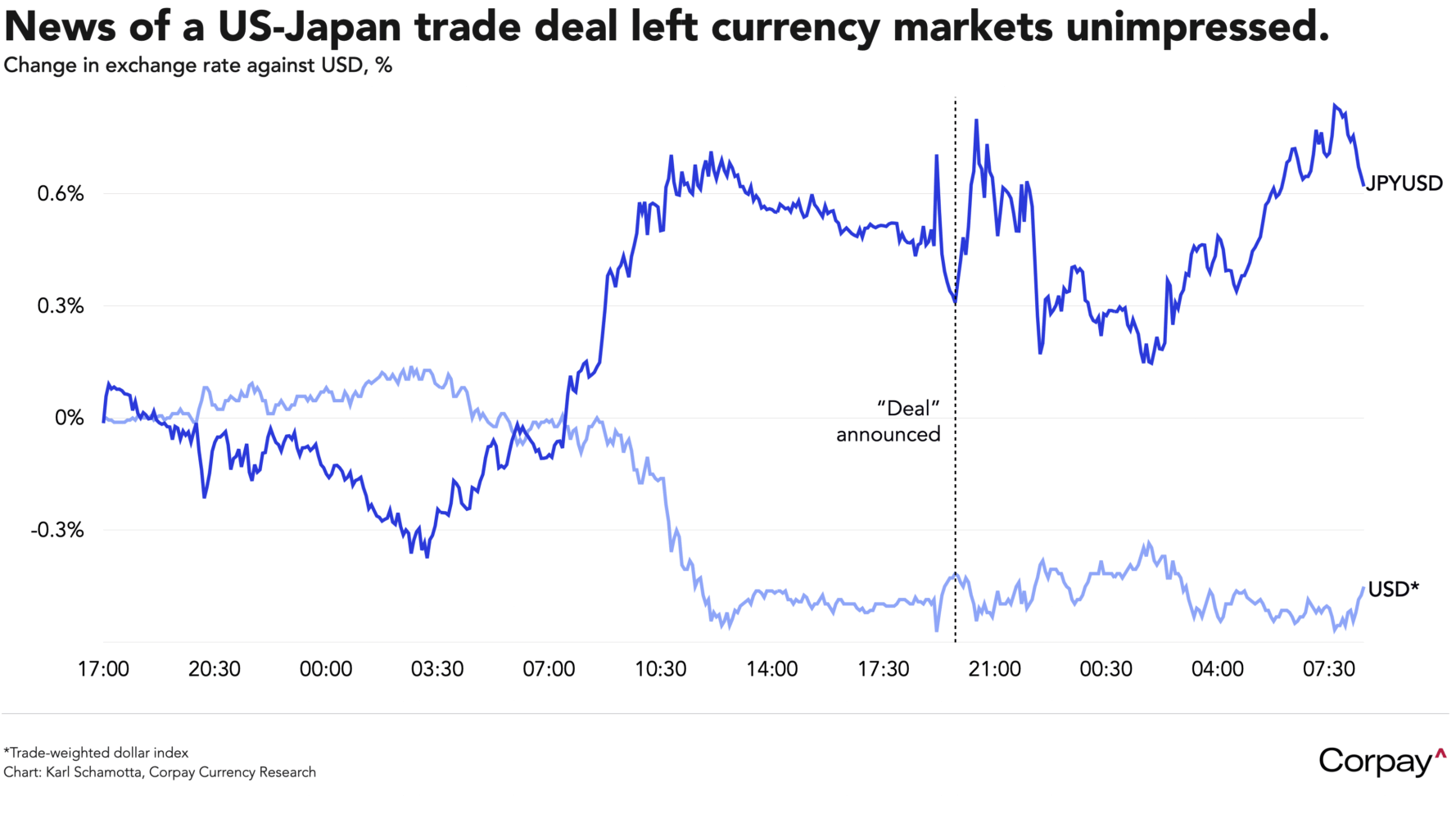

In a social media post last night, President Donald Trump announced a deal that would set tariffs at 15 percent on imports of most Japanese products into the United States—a threshold lower than the 25 percent previously threatened. Under what Trump called the “largest trade deal in history — maybe the largest deal in history*,” Japan will open its markets to American products, including cars and trucks, rice, and other agricultural products, and invest an additional $550 billion in US assets. Details weren’t provided on many of the specifics, but economists suspect that much of the purported new investment would be allocated to liquified natural gas projects already underway. The Nikkei index climbed when Tokyo’s chief negotiator, Ryosei Akazawa, later clarified that separate “national security” US levies on autos, which had risen to 25 percent, would also be lowered to 15 percent. However, moves in the yen were relatively contained, pointing to a more nuanced reception among currency traders.

We think this reflects a sobering reality, in which the proposed deal could improve Japan’s competitiveness vis-a-vis China, but isn’t likely to prove terribly beneficial to the economy over the long run. Chinese exports have cut into Japan’s global market share throughout the 21st century—far more than they have hurt the US—and this could reverse to some degree if current tariff differentials remain intact. But higher import levies on the American side will undoubtedly hurt revenues at some of Japan’s biggest firms, weighing on growth in the years ahead.

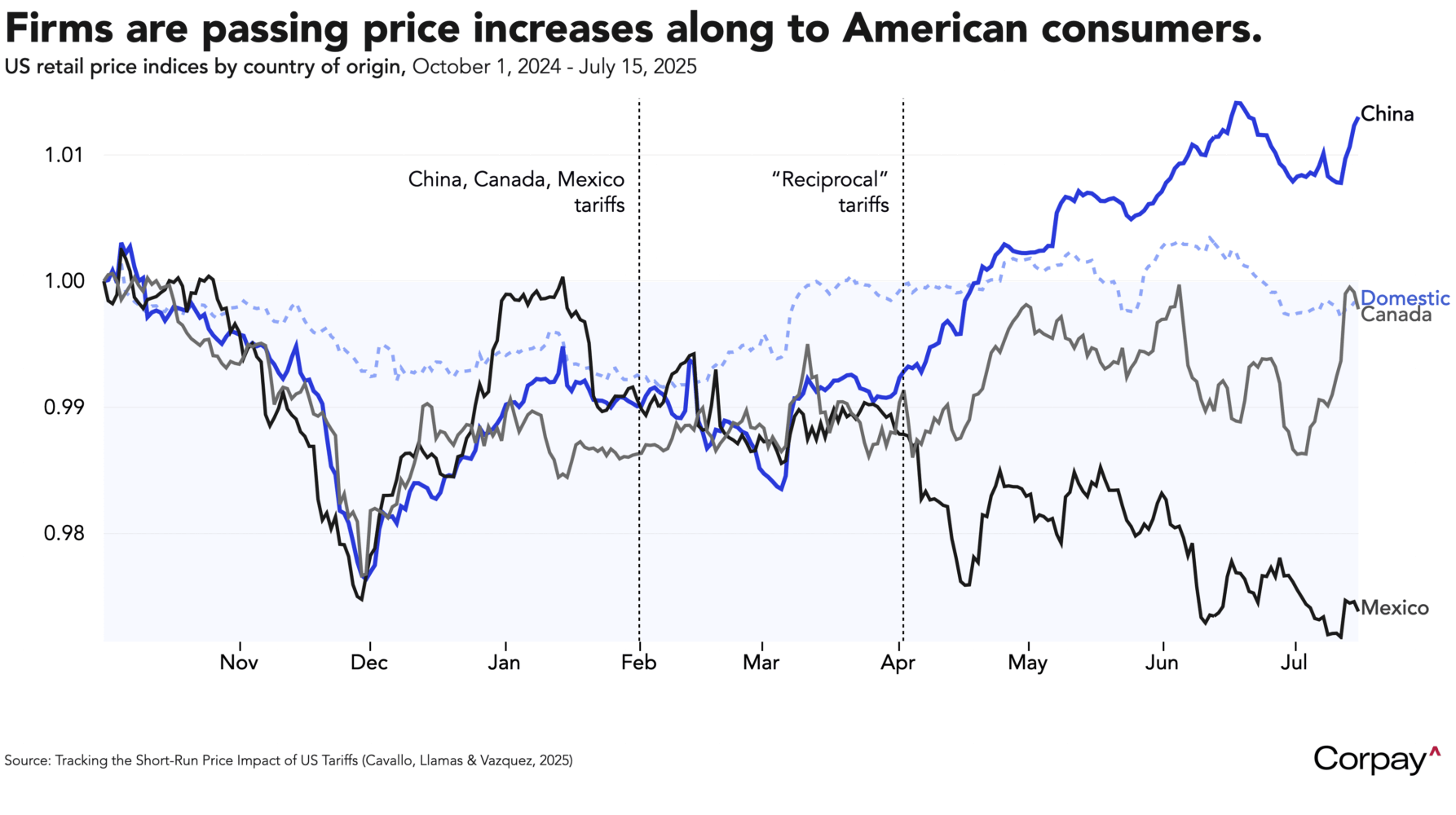

In the US, the burden on businesses and consumers is growing. Data releases in recent weeks have shown that prices paid to foreign suppliers have remained broadly stable, meaning that companies based outside the US have not agreed to offset tariff increases with discounts. Instead, firms in the US are absorbing a hit to profit margins—as exemplified in yesterday’s disappointing earnings guidance from General Motors—and passing cost increases on to their customers. Retail prices on products imported from China, as measured by Harvard’s Pricing Lab, have risen sharply since February, and are likely to climb further in the months ahead as front-running efforts run their course and inventories are wound down. Similar effects are probable in product categories imported from other countries subject to the president’s “reciprocal” tariff regime.

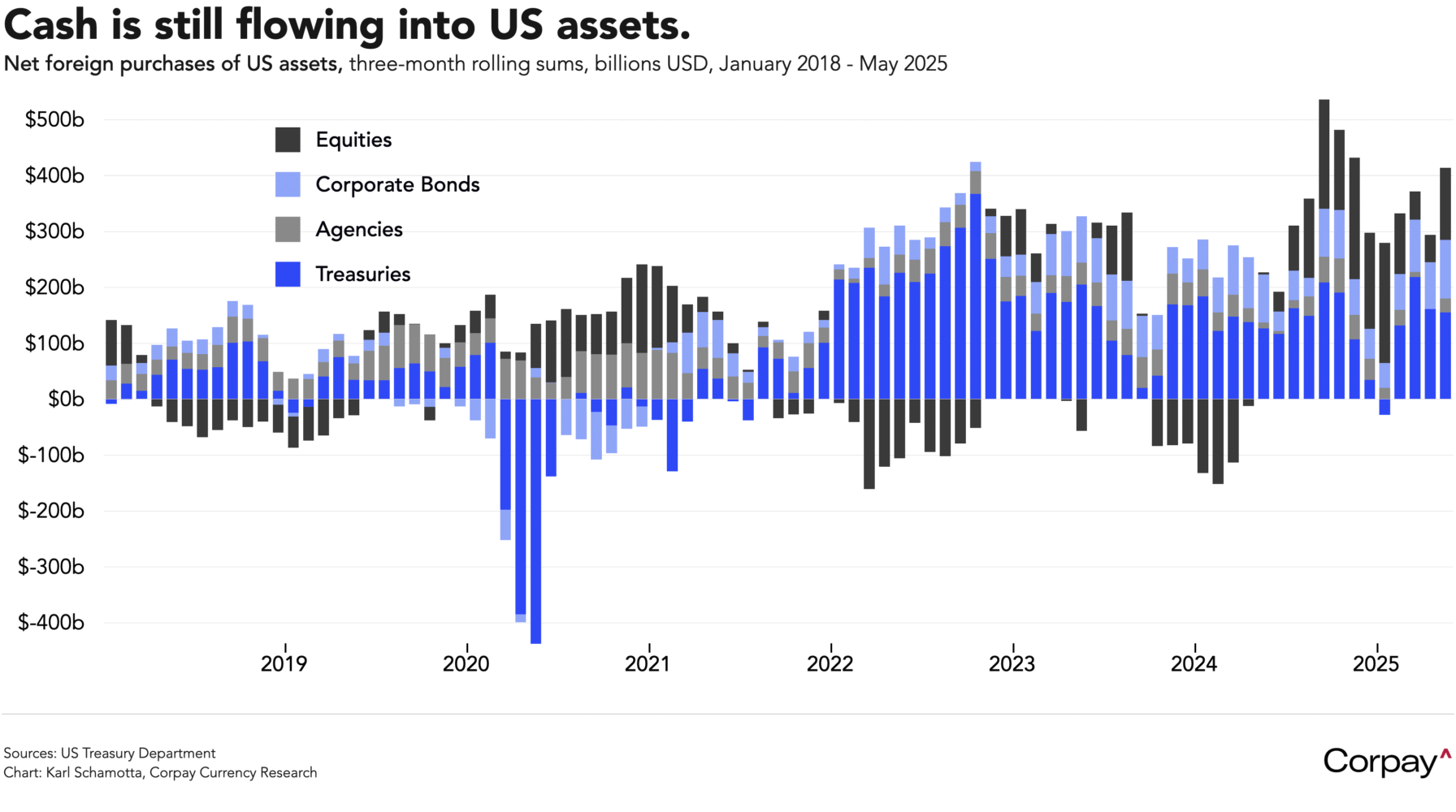

But, despite a lot of commentary to the contrary—some of it provided here in this newsletter**—there has been no clear impact on flows into American financial markets. According to somewhat-lagged data provided by the Treasury Department, demand for US assets rebounded among foreign buyers in May after a modest decline in April, suggesting that the post-“Liberation Day” selloff represented a tactical adjustment among global asset managers, as opposed to the beginning of a long-term reallocation toward markets elsewhere. This could change, particularly if the administration keeps up its attacks on the Federal Reserve’s independence—there are some signs that the “risk premium” embedded in American assets is climbing as markets brace for more inflation ahead—but thus far, the consequences for currency markets have not proven durable.

*A certain Commodore Perry may disagree.

**To put it more bluntly, my initial views on de-dollarisation are looking overwrought and misguided. I will nonetheless remain a disciple of former Fed chair Paul Volcker, who said: “There is a prudent maxim of the economic forecaster’s trade that is too often ignored: Pick a number or pick a date, but never both”. I do think global investors will ultimately diversify outside the US, but suspect it will take a long time to show up in measures of cross-border capital flows.