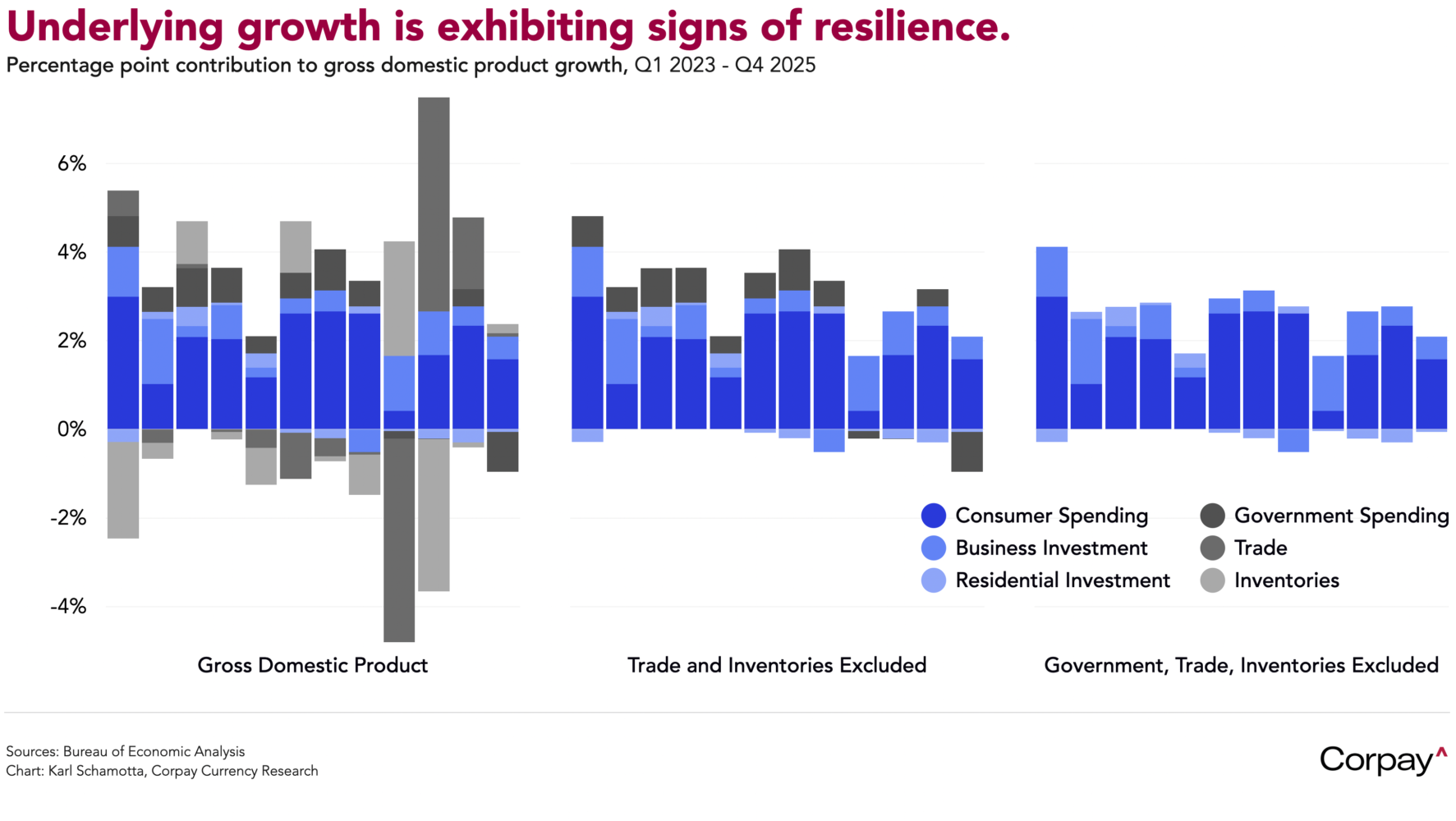

The American economy slowed by more than expected in the final quarter of 2025, with weaker consumer spending, trade effects, and the government shutdown combining to sap momentum. Data released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis this morning showed gross domestic product rising at a 1.4-percent annual rate in the fourth quarter after a 4.4-percent jump in the three months prior, surprising economists who had anticipated a print closer to the 3-percent mark. Household spending decelerated to a 2.4 percent pace from 3.5 percent previously, net exports flatlined as tariff front-running effects continued to offset themselves, and the government shutdown subtracted a full percentage point from the headline print. On a full-year basis, the economy grew at its slowest pace since the pandemic, expanding 2.2 percent in real terms after growing 2.8 percent in 2024.

However, measures of underlying growth remained relatively robust. Final sales to private domestic purchasers—sometimes seen as a cleaner read on underlying fundamentals—climbed at a respectable 2.4-percent pace in the fourth quarter. With government spending set to mechanically boost growth in the current quarter, and other tailwinds coming in, we suspect the economy’s momentum will hold up in early 2026.

Separately, the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation measure rose by the most in a year in December, making it more difficult to justify an aggressive course of rate cuts in the months ahead. According to data also published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the core personal consumption expenditures index rose 0.4 percent from the prior month—topping market forecasts for a 0.3 percent increase—and accelerated to 3.0 percent on a year-over-year basis. The overall personal consumption expenditures index climbed 0.4 percent relative to the prior month, and was up 3.0 percent from a year ago, accelerating from 2.8 percent in November. Personal income rose 0.3 percent month-over-month, and inflation-adjusted household spending climbed 0.1 percent, with both matching consensus projections.

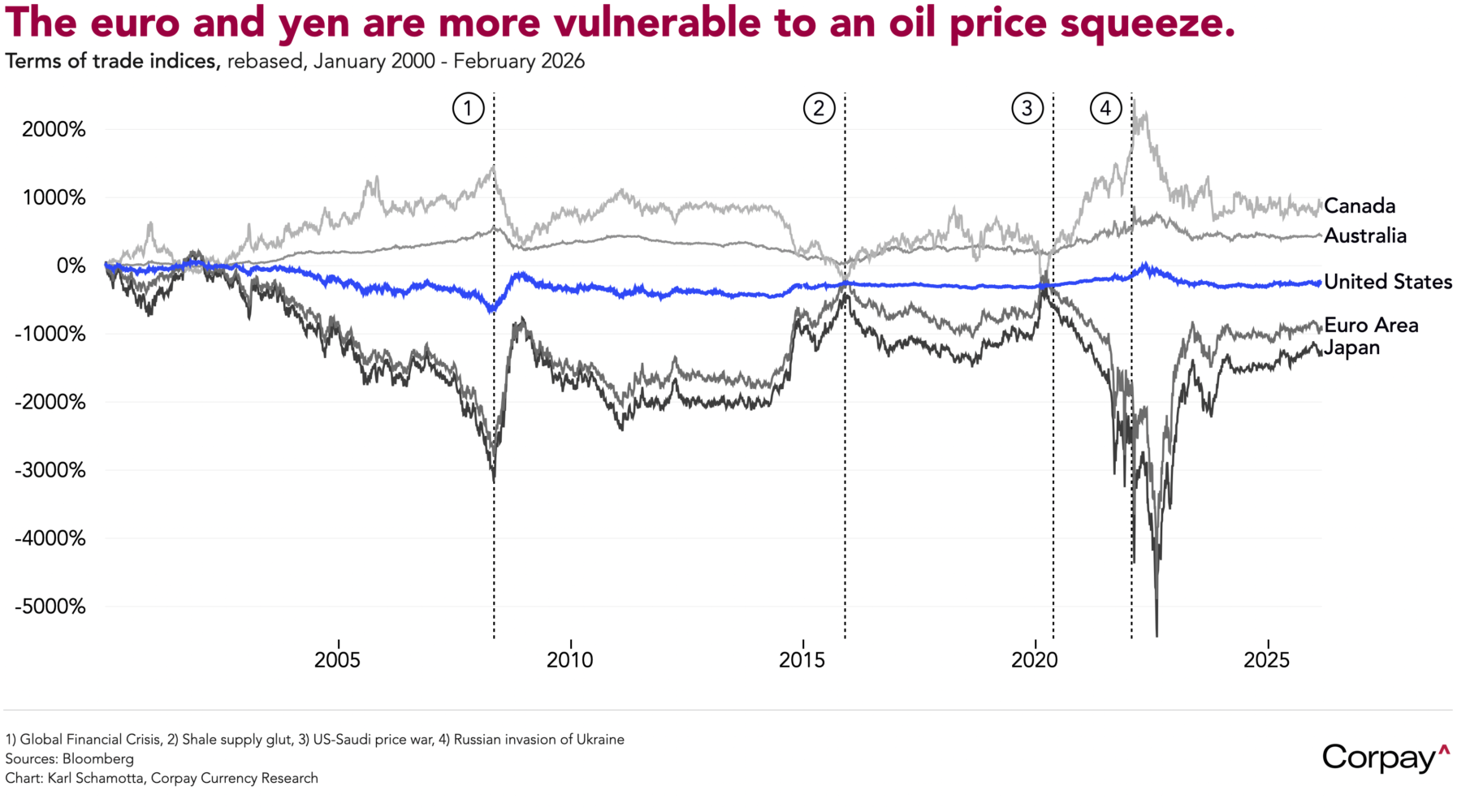

The dollar is on track for its strongest weekly gain since November, supported by a string of relatively-firm data prints, a modest tightening in policy expectations and a mild flight to safety as traders trim risk on reports the US could launch limited strikes on Iran as soon as tomorrow. After a multi-decade surge in unconventional production, the US has come closer to reaching energy independence and is seen as more insulated from oil price shocks than Japan or the euro area. Treasury yields are holding firm, and equity futures are setting up for a softer open.

The Canadian dollar is trading off its earlier lows after retail sales improved by more than expected in January, marking a hopeful handoff to the first quarter. An advance estimate provided by Statistics Canada this morning showed receipts at the country’s retailers jumping by 1.5 percent in the first month of the year after ending 2025 on a soft note, with a -0.4-percent decline in December bringing the fourth quarter to an almost-unchanged 0.1-percent gain. Despite (or, perhaps as a result of*) soaring levels of policy uncertainty, consumers kept spending through much of last year—driving a 4 percent rise in overall outlays in 2025—and this year seems to be kicking off in an even stronger fashion.

A Supreme Court ruling on President Trump’s use of emergency powers to impose tariffs could see trends reverse across several major pairs. It’s impossible to predict how markets will react to the decision—which could come as soon as 10 am this morning—given the range of possible outcomes and the administration’s plans to reimpose levies under alternative legal frameworks. Still, the decision could trigger turbulence in long-term yields and the dollar as firms seek refunds, importers rush to front-run new tariffs, Treasury funding expectations shift, and policy uncertainty rises once again.

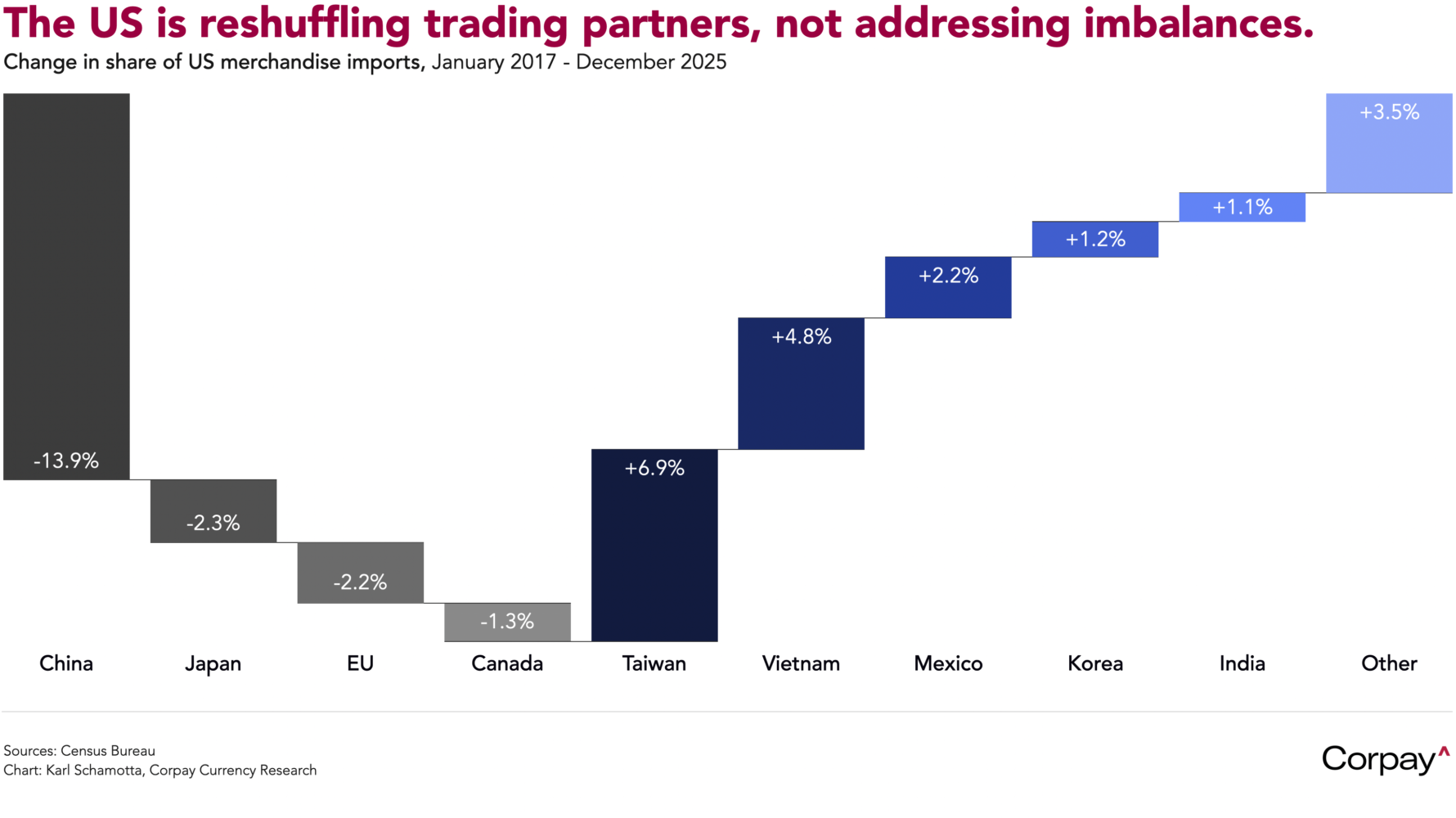

But the ruling is unlikely to alter the deeper capital flow calculus underpinning currency markets. After nearly a decade spent loudly implementing protectionist policies, the US has not reduced its external deficits so much as it has reshuffled them geographically, confirming what orthodox economic theory would suggest: that a meaningful adjustment in trade imbalances cannot occur without a shift in domestic spending and investment patterns. Fixing this would entail running smaller fiscal deficits, tax reforms that favour retained earnings and saving over debt-fuelled consumption, fewer incentives for foreign capital to flow into US financial assets and property, and industrial policies that expand tradeable-sector capacity without inflating asset prices—an agenda that currently enjoys limited support and is likely to face stiff resistance from entrenched interests. For now, the US will continue borrowing from abroad and consuming more than it produces.

*”Retail therapy” is a real thing in my household.