Treasury yields are climbing and the dollar is under pressure after Bloomberg reported that Chinese regulators have instructed the country’s commercial banks to cut their holdings of American government debt, noting threats posed by “concentration risks and market volatility”. According to the report, officials verbally advised financial institutions to reduce new purchases and scale down existing positions in recent weeks. Benchmark ten-year yields are up five basis points, and the trade-weighted dollar is down roughly half a percent.

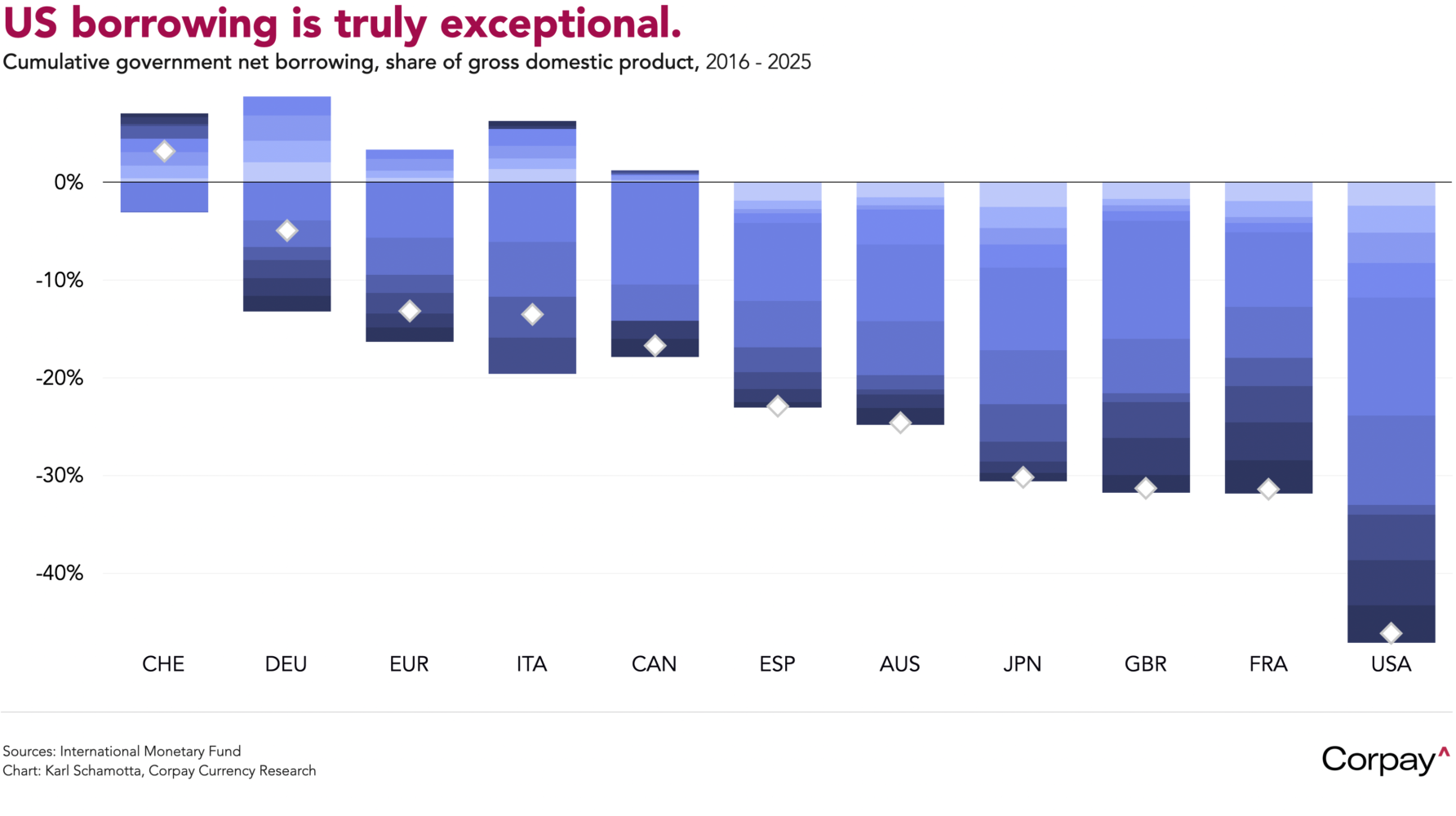

The policy shift is less dramatic than the headline suggests—implying that the kneejerk market reaction should fade—but is important nonetheless. Even when offshore custodial holdings are included, China’s official stockpile of Treasury instruments have fallen sharply over the last decade as the country has taken a less activist approach to currency intervention, and its banks have also lost market share, now controlling less than 1 percent of outstanding marketable US debt. The directive however reflects growing awareness among central banks, regulators and asset managers of the risks associated with the world’s over-reliance on the US financial system—a danger Mark Carney flagged in a 2019 speech. If participants gradually reduce debt purchases and chip away at the dollar’s dominance in trade invoicing and global finance, a more multipolar system could emerge, constraining America’s ability to run manifestly unsustainable fiscal deficits*.

Across the Pacific, the yen is modestly firmer** after Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi won a sweeping landslide in the weekend’s snap election. Her Liberal Democratic Party secured 316 of 465 seats in the lower house, its most decisive result since the party’s founding in 1955, vindicating her decision to call the early vote. With a two-thirds supermajority, Takaichi now has scope to override the upper chamber, potentially clearing the way for expansive fiscal measures and constitutional reform, and giving Japan a degree of political stability rare among advanced democracies.

To us, the election result symbolises a deeper transformation underway in the Japanese economy’s relationship with global capital markets. The country is, at last, emerging from decades of deflation and asset-price stagnation, and more expansionary fiscal policy should support growth, generating positive tailwinds for earnings and equities. Reforms in the corporate sector are making Japanese investment more attractive to both domestic and overseas capital, and a steepening yield curve is offering the prospect of more compelling opportunities ahead.

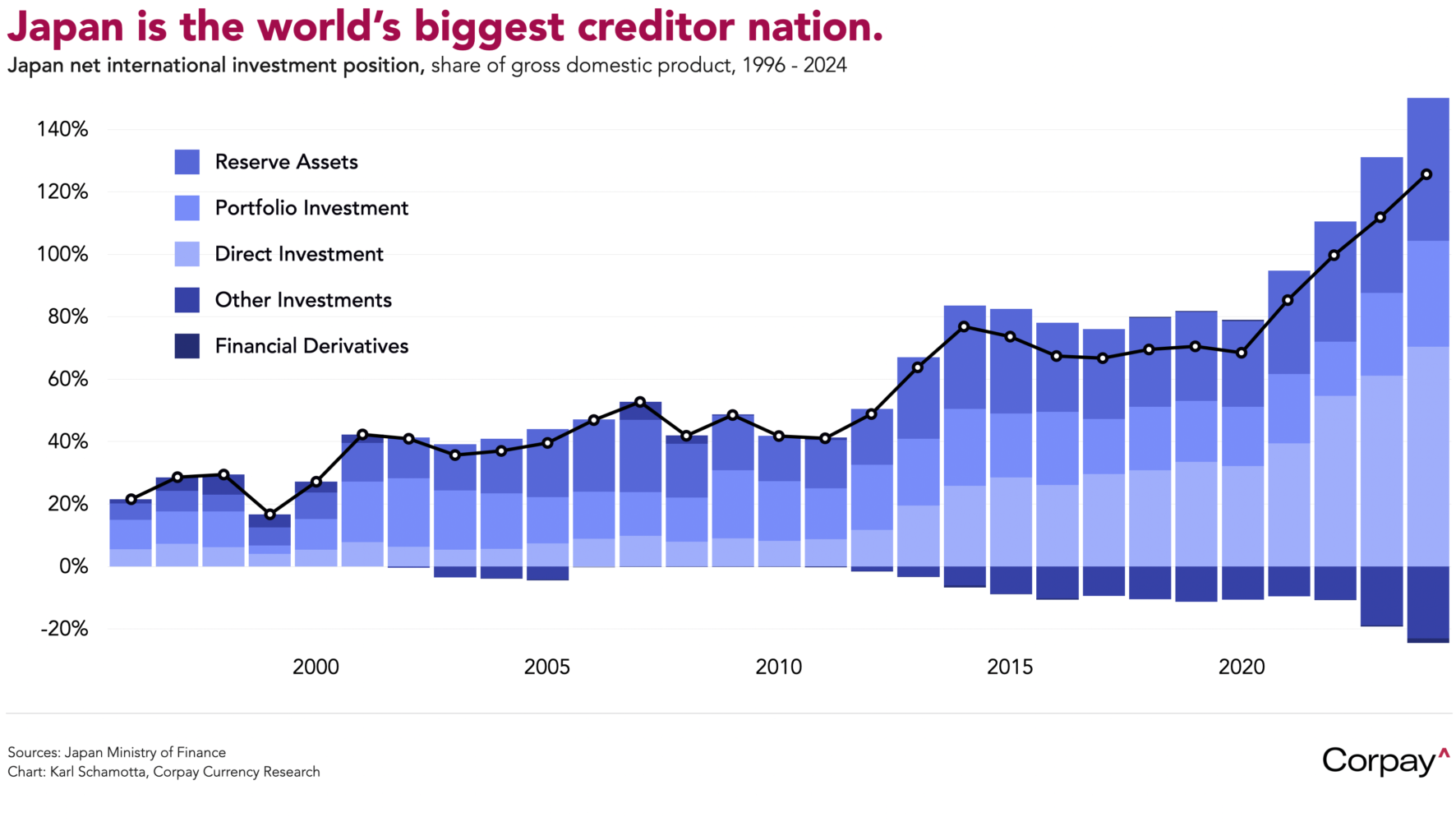

This matters enormously for currencies because of Japan’s unique structural position. After running current-account surpluses for decades, Japan has emerged as the world’s largest creditor nation, with a net international investment position that has grown to an all-time high as a share of gross domestic product—the total value of financial assets held by Japanese investors abroad far exceeds the value of Japanese assets held by foreigners. Many segments of the economy are running what are, in effect, short-yen, long-dollar positions, meaning as domestic yields rise and growth improves, repatriation flows could begin to build. Political clarity and a stronger outlook may also attract foreign capital. A yen recovery—paired with an attendant decline in asset prices elsewhere—cannot be ruled out.

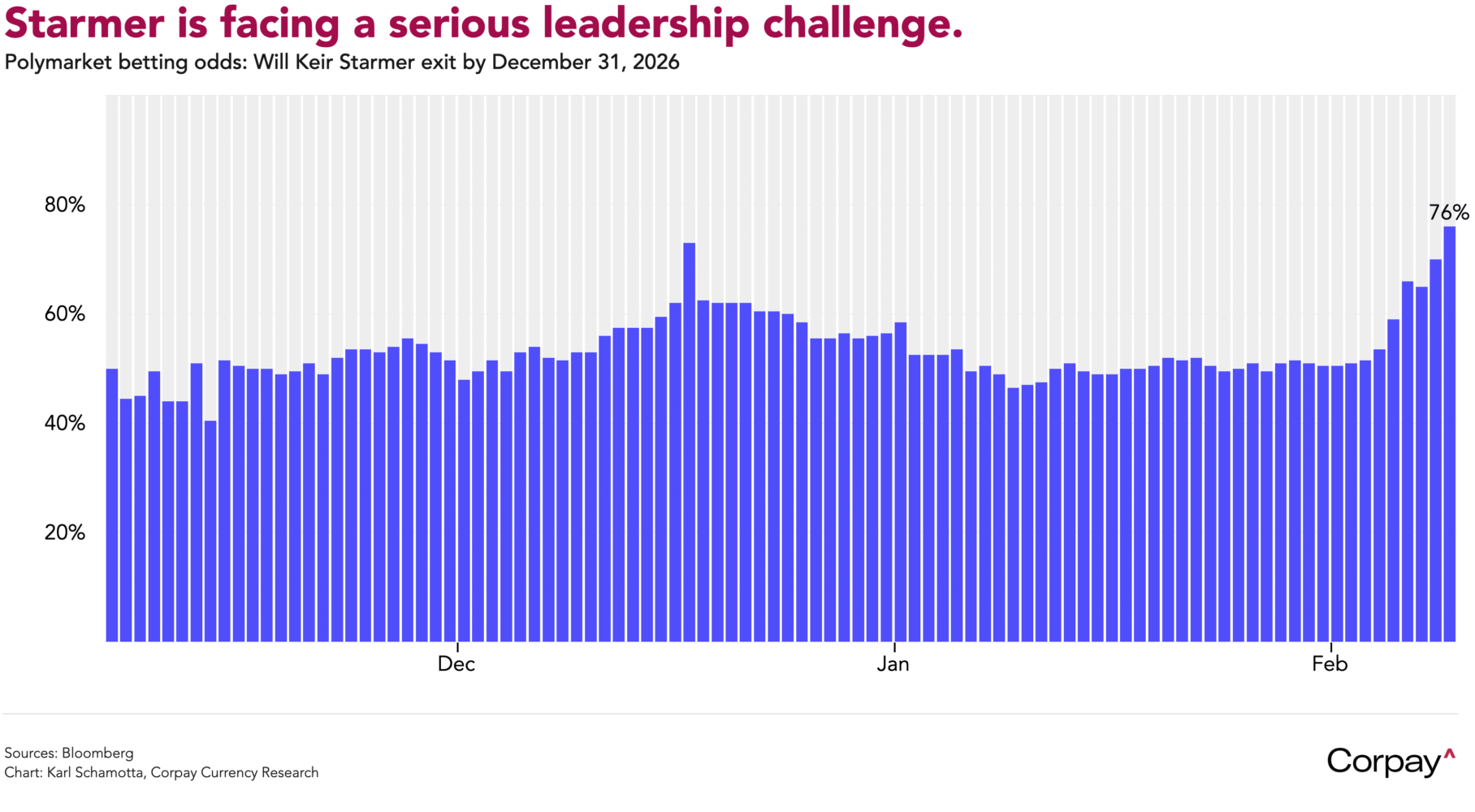

In London, gilt yields are rising and the pound is trading with a distinctly defensive bias as the political crisis engulfing Keir Starmer deepens. Morgan McSweeney, Starmer’s chief of staff, and the strategist widely credited with engineering Labour’s 2024 landslide, resigned over the weekend, saying he took “full responsibility” for advising the prime minister to appoint Peter Mandelson as ambassador to the United States despite Mandelson’s known links to Jeffrey Epstein. Tim Allan, director of communications, stepped down this morning. The Mandelson affair—now the subject of a Metropolitan Police criminal investigation after newly released files appeared to show the former minister leaking market-sensitive government information to Epstein during the 2008 financial crisis—has become a serious threat to Starmer’s premiership, with prediction markets giving him 76 percent likelihood of leaving before year end.

The political turbulence comes after the Bank of England turned distinctly more dovish. Last Thursday, the Monetary Policy Committee avoided cutting rates by the narrowest of margins, surprising investors who had expected most policymakers to favour staying on hold. Swaps traders are now putting 96-percent odds on a move in April, and a second move by year-end is firmly in play.

A dense slate of American economic data releases should give markets plenty to chew on in the coming days, particularly after last week’s raft of soft labour market prints put downward pressure on yields. A shutdown-reshuffled calendar will see December retail sales out tomorrow, last month’s all-important non-farm payrolls report on Wednesday, and January’s consumer price index on an inauspicious Friday the 13th. The combined numbers are expected to support the case for two rate cuts by year end, but will undoubtedly suffer from statistical adjustment and data collection issues that obscure underlying fundamentals.

More broadly, implied volatility has risen from January’s unusually-low levels as investors question the US outperformance, technology-driven growth, and superabundant liquidity narratives that supported speculative assets for much of the past year. We doubt the adjustment is complete. With the global order showing renewed signs of strain—Beijing reducing exposure to US financial markets, Tokyo transitioning out of a decades-long slump, and Western capitals coming under intensifying political attack—currency markets are only beginning what could be a long and turbulent period of repricing.

*Alexis de Tocqueville reputedly said, “The American Republic will endure until the day Congress discovers that it can bribe the public with the public’s money,” but Congress found it could bribe the public with borrowed foreign money instead. This has underpinned US exceptionalism for decades, but may not last forever—as Margaret Thatcher observed, “The problem with Socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money.”

**That the yen picked up fewer yards than the Patriots may reflect market positioning ahead of the vote, her calming words after the victory, or the dollar’s broader decline.