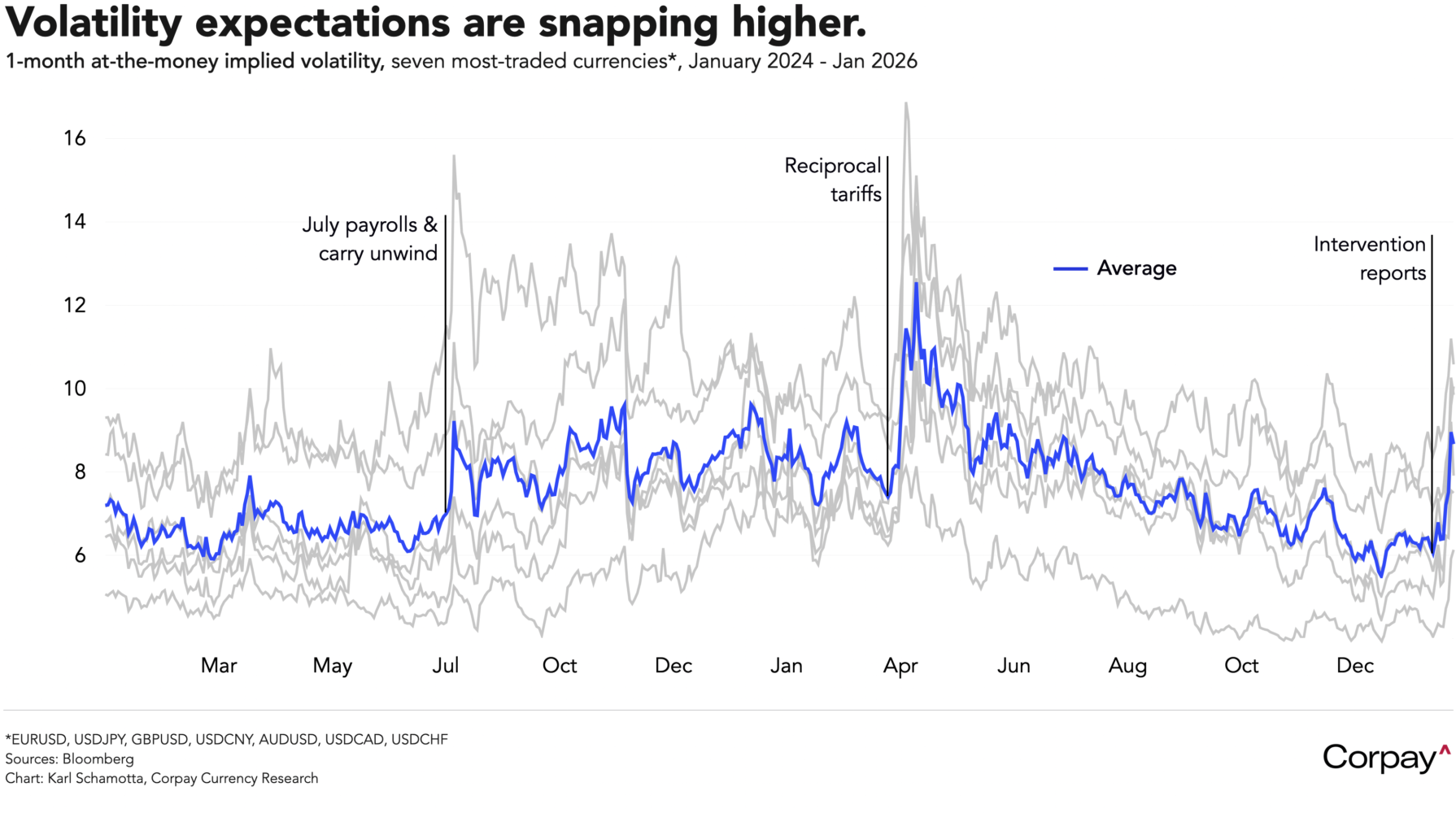

Good morning. The almighty greenback is struggling to climb off a four-year low after US president Donald Trump said he didn’t think it had fallen too far, remarking that he could make it “go up or go down like a yo-yo,” but that it’s “doing great”—comments widely read as an endorsement of further weakness. A softer dollar could support US exports and raise import prices*, consistent with Trump’s aim of narrowing trade deficits, but it also risks generating market dislocations and raising borrowing costs if real-money investors redirect capital elsewhere. Treasury yields are holding firm, equity futures are setting up for a positive open, and measures of implied volatility in currency markets are climbing as market participants brace for more turbulence ahead.

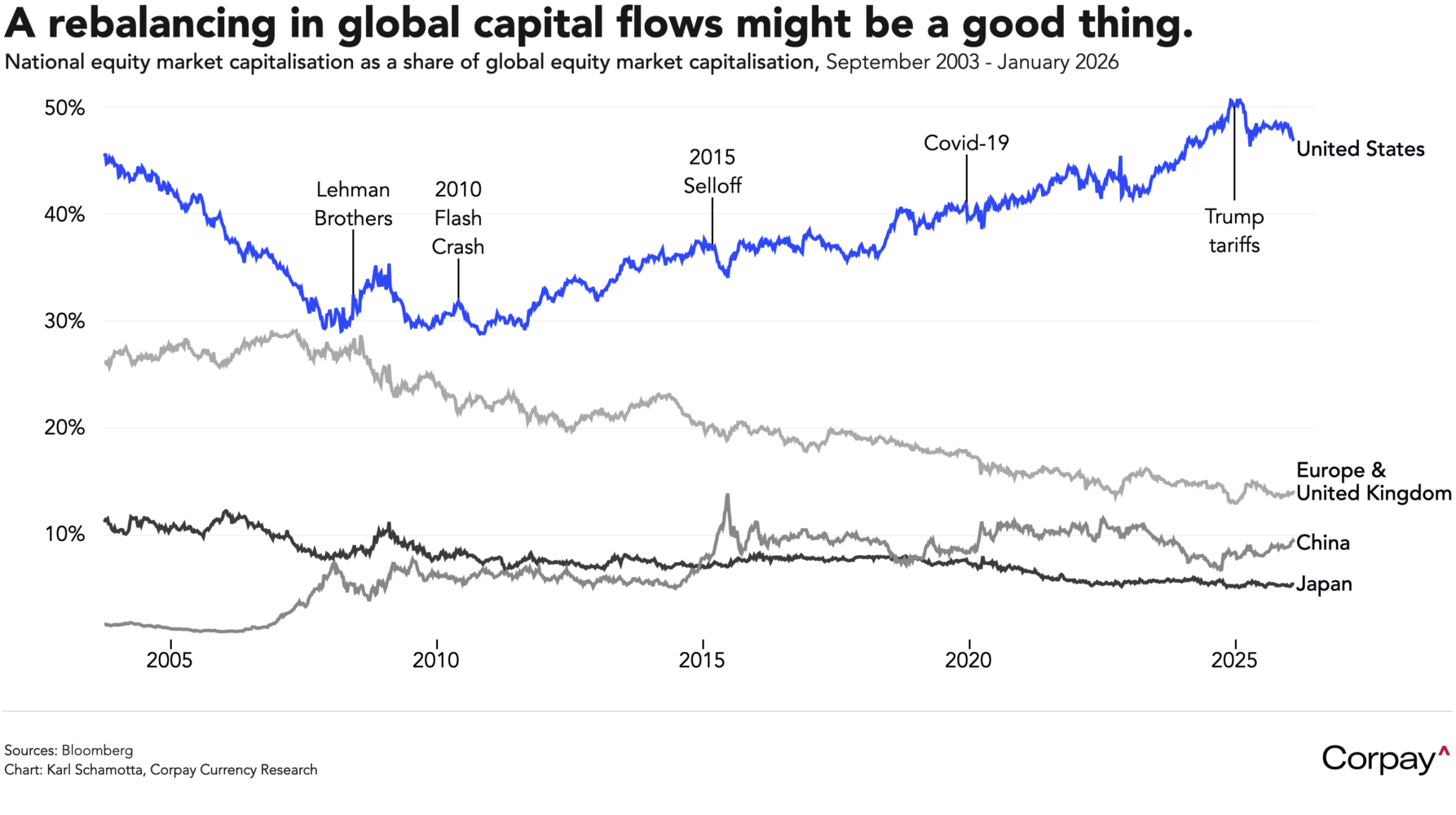

The president’s remarks are the clearest signal yet that the administration has abandoned the decades-old “strong dollar” orthodoxy, and that global investors will have to accept a higher degree of risk when deploying capital in US markets. This might lead to a deeply-disruptive reversal in inward financial flows in the short term, but could prove beneficial for the global economy over time. By some measures, the US absorbs more than 40 percent of global gross capital flows and accounts for nearly 47 percent of equity market capitalisation—far above its share of world output. A partial redeployment of some of that capital elsewhere would narrow trade imbalances, spread growth more evenly and, over time, reduce the risk of major global dislocations.

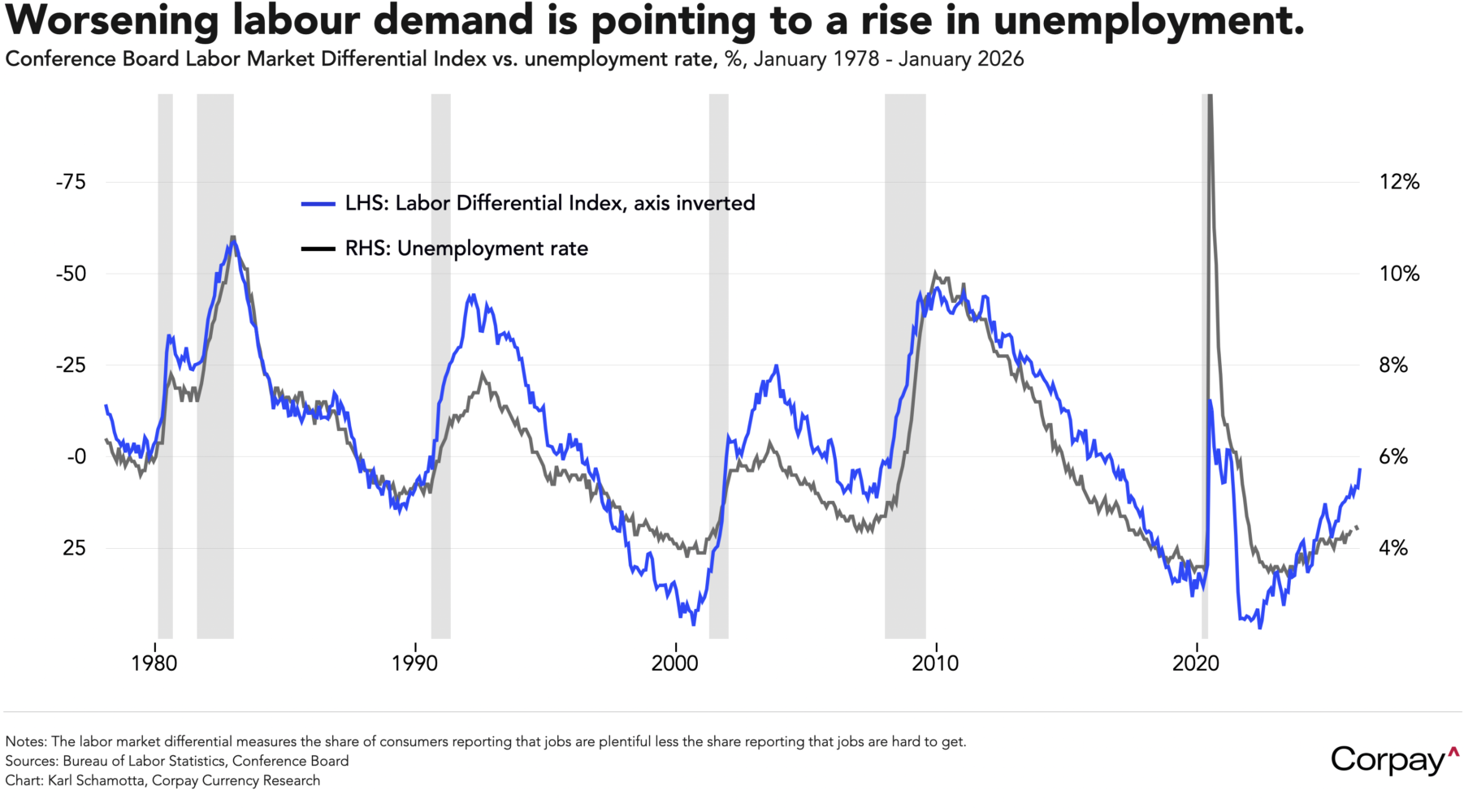

The Federal Reserve is overwhelmingly expected to stay on hold later today, meaning that Jerome Powell’s language during the post-decision press conference will be critical in setting market direction. Investors will scrutinise his assessment of labour markets, inflation and growth, as well as his take on the widening gap between weak sentiment and resilient data—a disconnect that was highlighted yesterday by a sharp drop in US consumer confidence. The Conference Board’s index fell to 84.5 in early January from an upwardly-revised 94.2 in December, marking its lowest level since 2014, including the pandemic. Concerns over inflation, tariffs, politics, healthcare costs and jobs drove the decline, while the labour differential collapsed to 3.1 from 8.4, signalling rising unemployment risks.

Powell’s remarks on the Fed’s independence are likely to draw particular scrutiny, especially if the White House chooses to make a nomination announcement shortly before or after the meeting. We do not expect that narrative to have a lasting effect on rate expectations, however, given the Fed’s relatively-effective defence in recent months and signs that the administration now favours a more pragmatic chair over overtly partisan alternatives. Absent the political backdrop, markets might well be pricing rate hikes rather than cuts, given continued economic resilience, inflation near the top of the target range, and still-loose financial conditions.

The Bank of Canada is widely expected to stay sidelined for a second consecutive meeting after delivering 100 basis points of cuts in 2025, with Governor Tiff Macklem likely to reiterate that policy is “at about the right level” absent a material shift in economic conditions. Underlying inflation remains subdued—despite supply-side pressures keeping food prices elevated—while economic momentum has clearly cooled, with growth increasingly reliant on net exports rather than domestic demand. Business surveys continue to signal fragility—particularly among trade-exposed firms grappling with tariff risks—while softer hiring intentions and rising layoffs should leave policymakers understandably sceptical of autumn’s surprisingly-strong jobs data.

Against this backdrop, trade uncertainty stands out as the dominant macro risk: any deterioration in Canada’s relationship with the US would make rate hikes later this year difficult to justify. Our baseline expectation is that the looming USMCA negotiations will come with a round of overheated rhetoric from the White House, meaning that the cloud of uncertainty currently hampering business activity is unlikely to lift anytime soon. To a degree, markets have moved to reflect this outlook—a late-2025 jump in monetary tightening expectations has now been largely wiped out—but we think they have further to go in pricing a dovish bias from the Bank of Canada. The loonie should continue to underperform its counterparts against the US dollar.

*Exchange rate passthrough—the degree to which exchange rate changes show up in domestic prices—has declined markedly in the US over time. In the 1970s and early 1980s—an era of high inflation and weaker policy credibility—dollar moves translated relatively quickly into prices. Since the mid-1990s, however, research and experience point to a much more muted effect: dollar depreciation typically lifts import prices by only a few percentage points and adds very little to core inflation over time. Several structural forces explain the shift: First, the credibility of the Federal Reserve’s inflation target anchors expectations, making firms reluctant to reprice. Second, globalisation and intense competition encourage margin compression rather than price hikes. Third, invoicing in dollars, longer-term contracts, and widespread hedging blunt the impact on corporate margins. As such, I would estimate that the administration would have to engineer a dollar decline exceeding 20 percent in order to deliver an appreciable reduction in trade deficits.